Oldest Schoolhouse for Black Children Moves to Colonial Williamsburg

The school educated free and enslaved Black children between 1760 and 1774

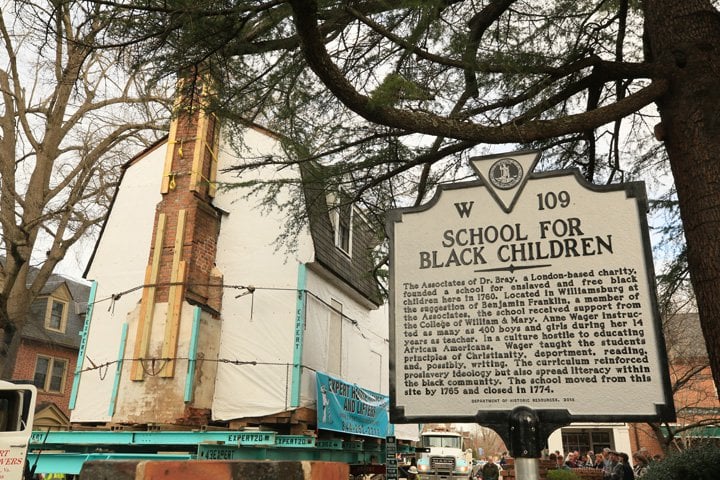

The oldest surviving schoolhouse for Black children in the United States has moved to its new permanent home in Colonial Williamsburg.

Last week, crews at the College of William & Mary carefully loaded the 18th-century building onto a flatbed truck and drove it to the site, just about half a mile away. Per the Virginia Gazette’s Sian Wilkerson, hundreds of spectators lined the route—which took over three hours to navigate.

The building most recently housed the university’s military science department. But about 20 years ago, Terry L. Meyers, a literary scholar at the university, started to wonder about its history. Since then, researchers have been poring over archival materials, conducting archaeological excavations and analyzing the building’s wood framing.

Two years ago, experts officially confirmed that the modest white building situated on William & Mary’s campus was once the Williamsburg Bray School, where free and enslaved Black children learned alongside one another from 1760 to 1774. According to William & Mary, it’s likely the oldest building of its kind in the country.

At its new location, it’s slated to open to the public in September 2024, the 250th anniversary of the school’s closing.

“The Williamsburg Bray School provides us with an incredible opportunity to explore and learn from a complicated piece of our past that—like the Bray School building itself—has been overlooked by so many for hundreds of years,” says Cliff Fleet, Colonial Williamsburg’s president and CEO, in a statement.

At the recommendation of Benjamin Franklin, a London-based charity opened the school in 1760. The charity was called the Associates of Dr. Bray—named for its founder, English clergyman Thomas Bray—and it opened several such schools throughout the colonies, with a goal of converting Black children to Christianity.

During its 14 years in operation, the Williamsburg school had just one teacher, a white woman named Ann Wager. All told, Wager taught the school’s faith-based curriculum to roughly 400 students between the ages of 3 and 10 years old. The building could hold up to 30 students at a time.

The majority of students, some 90 percent, were enslaved. Ultimately, the curriculum “justified slavery and encouraged those who were enslaved to accept their destinies,” writes Colonial Williamsburg.

At the same time, the lessons—which included reading, writing and sewing—provided enslaved children with an education at a time when many white communities prohibited such practices, “fearing literacy would encourage their liberty,” per Ben Finley of the Associated Press (AP).

The school’s story challenges popular notions about slavery in the 18th century, says Matt Webster, who directs architectural preservation and research at Colonial Williamsburg, to the Washington Post’s Susan Svrluga.

“It’s also a very powerful story about education, and the power of education,” he adds. “Once you educate someone, you can’t really control what they do with that.”

The school shut down during the American Revolutionary War, and the building became a private home. William & Mary later purchased the building and began using it for university functions. Crews installed electricity and built new additions. However, they left many of its original features intact, including the floorboards, chimney and staircase.

In the fall of 2021, the university agreed to sell the building to Colonial Williamsburg, which will restore it to its original state. Together, the university and the museum launched the Williamsburg Bray School Initiative to support ongoing research, restoration and interpretation efforts.

“It’s incredible to see how this has unfolded,” Meyers, who is now retired, tells the Virginia Gazette’s Wilford Kale. “I had no idea it would take the turn it did.”