Mina Miller Edison managed a large estate, ran countless charities, raised six children, had an encyclopedic knowledge of birds, and dedicated herself to the theory and practice of women’s labor. Her husband’s achievements were similarly wide-ranging: He was the inventor Thomas Edison, pioneer of incandescent light, holder of 1,093 patents, architect of America’s technological transformation and a notorious workaholic. Yet few know the story of the other workaholic Edison—the woman heralded by newspapers as “the one ‘boss’ that [Thomas] obeys.” Mina, who presided over Glenmont, the Edisons’ home in West Orange, New Jersey, for six decades, is half the story of how the Edison family helped define American modernity.

Born in Akron, Ohio, in 1865, Mina was the 7th of 11 siblings. Her father, Lewis Miller, was an inventor and prominent figure in 19th-century Methodist education reform. In addition to attending lectures at the experimental Chautauqua Institution, which her father co-founded, Mina graduated from high school, went to finishing school in Boston and traveled with her siblings. She was on track to become an ordinary upper-middle-class wife. Then she met Thomas.

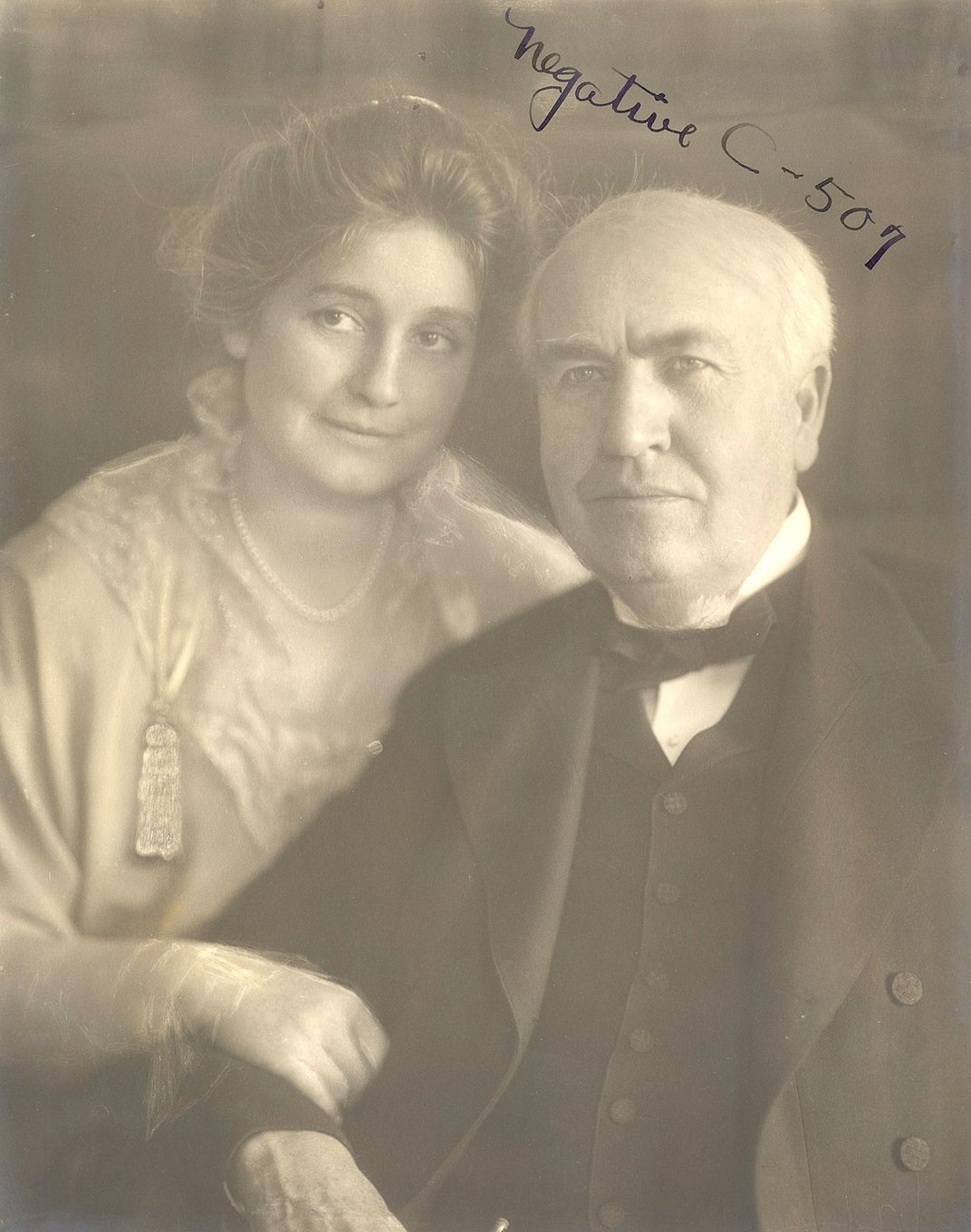

The year was 1885. Thomas’ first wife, Mary, had died the previous year, and he had three children at home. Thomas was smitten with Mina, noting in his diary that he might have to take out an accident policy because he was “thinking about Mina and came near [to] being run over by a street car.” Still, he remained smooth enough to flirt in Morse code, even proposing by tapping out the question.

By the time the Edisons settled into their new home in 1886 (purchased at half price and fully furnished because it had been confiscated from an embezzler), Thomas had already established his reputation as the “wizard of Menlo Park.” As Mina, startled by her sudden celebrity status, wrote to her mother from her Florida honeymoon, “People stare at us so.”

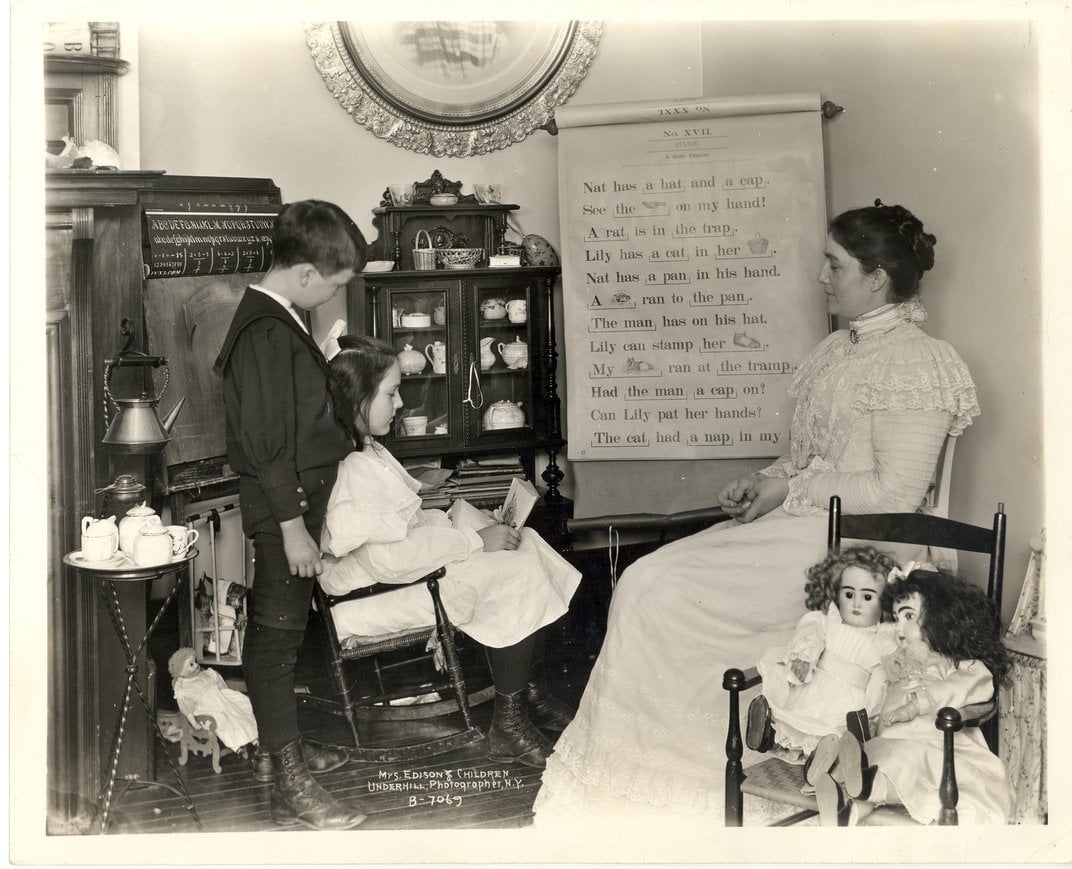

Being “Mrs. Thomas A. Edison” was a lot of work. Mina had to manage the public entertainments peculiar to technological royalty, including putting up with Henry Ford and panicking when the king of Siam asked for iced tea. She also had to fulfill all the domestic duties expected of a wife. The 20-year-old was suddenly in charge of a giant house and three stepchildren: Marion, Thomas Jr. and William. (Her children with Thomas—Madeleine, Charles and Theodore—would follow over the next 12 years.) It didn’t help that Mina had a hard time winning over 13-year-old Marion, who thought the “Ohio girl” “too young to be a mother to [her] but too old to be a chum.”

Mina leaned on her own mother and sisters for support. “I know there [are] many things demanded of you,” wrote her sister Jennie Miller in 1886, “but you are strong and have character enough to stand way above them. … I know of no one who could do better.” Even when Mina struggled under pressure, her family never saw her as a “whiner,” says great-grandson David Sloane, who remembers meeting her at the very end of her life. “She had a job that was larger than human-sized.”

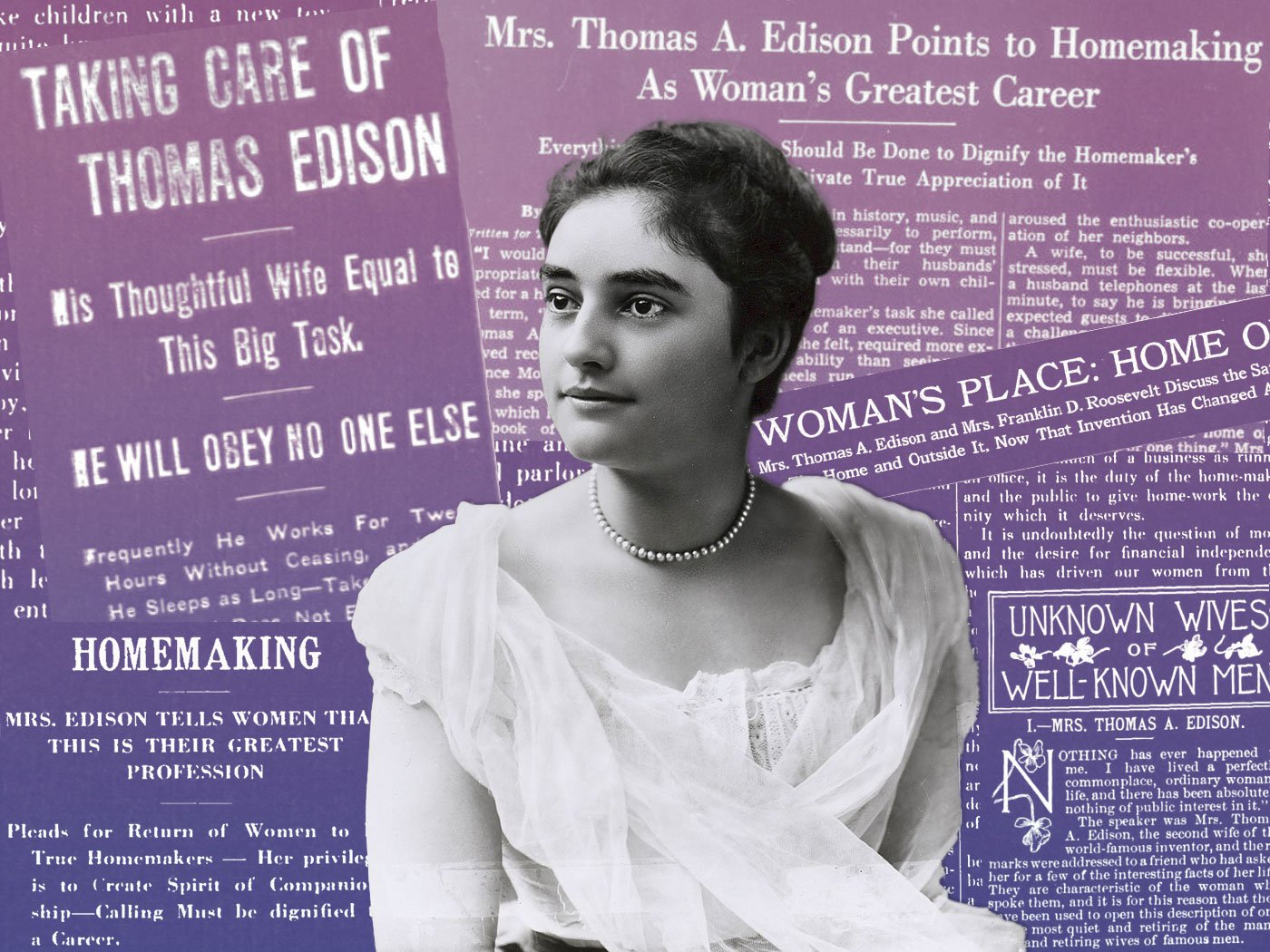

Over the course of her marriage, the young woman once perceived as the “simple, quiet wife of a great and successful man” (to steal a never-quite-accurate description of Mina from the Ladies’ Home Journal) transformed into a confident public figure who called herself a “home executive” and promoted domestic labor as a matter of national importance.

As the United States industrialized in the 19th century, paid (male) labor moved increasingly outside of the home. Middle-class homes were idealized as protected (female) havens, sheltered from the bustle of capitalist production. These heavily gendered “separate spheres” were mutually reinforcing: Wives performing unpaid work within the home were markers of their husbands’ financial success. The supposedly protected home, however, was never static. New household technologies, whether apple parers or washing machines, raised questions about what kinds of work women should be doing.

In 1912, Thomas himself told Good Housekeeping he hoped technology would liberate women from “household drudgery,” which he suggested—among other gendered and racialized comments on so-called progress—had kept women from developing their brains for centuries. (His vision of an electrically powered home, running to the sounds of phonograph music, was essentially a self-advertisement.)

Mina experienced these economic and technological changes firsthand. She married at the height of the Gilded Age, when electric light was still a novelty. While at Glenmont, she watched ten presidents come and go. She took part in temperance activism. She weathered World War I, witnessed women winning the vote and lived through the Great Depression. Upon her death in 1947, she left behind a world blighted by World War II and the atomic bomb. She is thus a remarkable historical barometer for understanding how large-scale changes in women’s work played out on an individual level.

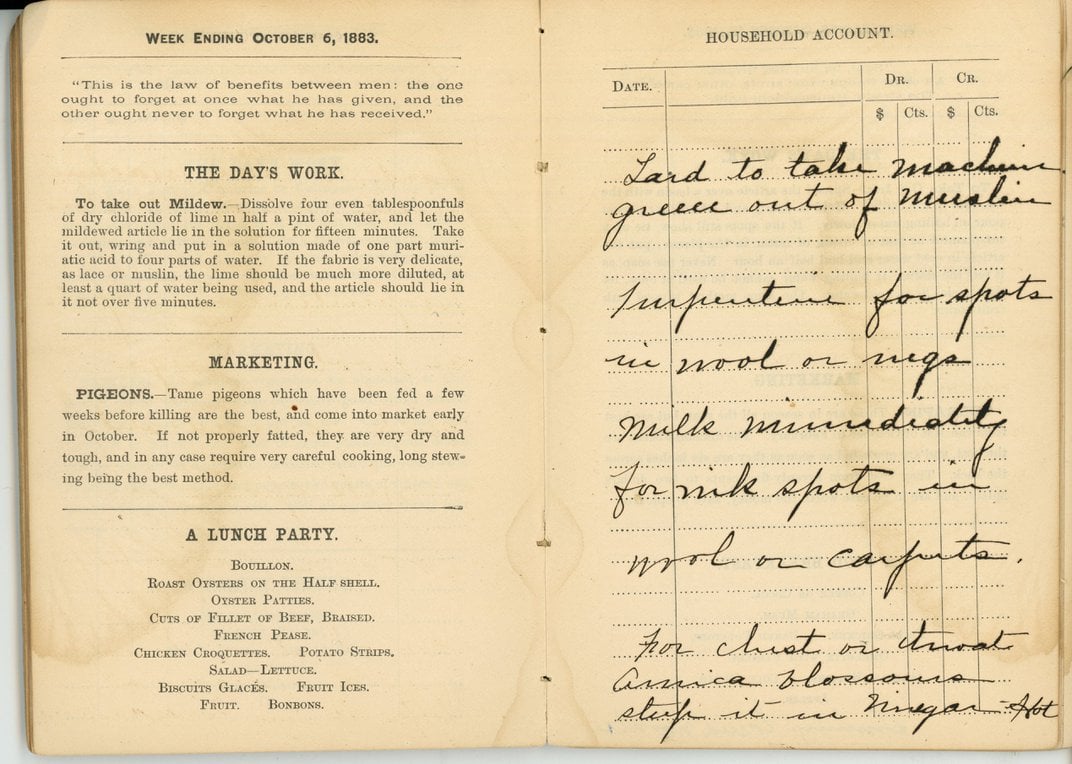

Nineteenth-century housekeeping was not for the faint of heart. Running Glenmont took practice. Mina read manuals on housekeeping and discussed domestic service with her parents. She learned tricks like using kerosene and varnish to eliminate bugs or treating machine grease stains with lard. Mina was never doing this work on her own: Her staff, whose exact composition fluctuated over time, regularly included a waitress, a cook, a maid, gardeners and a chauffeur, and she often outsourced the notoriously rough job of laundry.

Not content to let her husband be the only scientist at Glenmont, Mina approached household management scientifically. This was nothing radical. Before Mina was born, women like Catharine Beecher had defined “domestic economy” as a discipline, emphasizing practical education for women and promoting housework as a “science” and “profession” that required significant training. Housework became science in a very literal sense when Ellen Swallow Richards, the first woman to graduate from MIT, started applying her knowledge of chemistry to everyday domestic problems, co-founding the American Home Economics Association in 1909. For Richards, the home was anything but a private domestic retreat; she hoped home economics would both advance women professionally and improve public policy.

Mina admired Richards all her life, even quoting her during a 1940 interview. By then, Richards had been dead almost 30 years, but Mina suggested that her call for “educated women” to promote and develop the “science of domestic economy” was still current. “Educated” was the operative term: “A knowledge of the elements of chemistry and physics must be applied to the daily living,” Richards once said. Mina modeled her own career on this blend of professionalism, study and intense personal investment.

Mina was always thinking about the home’s social importance, and she wielded her considerable resources to meet every new crisis. When the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, home economics became crucial to national security. Wartime inflation made it difficult for people to feed their families, and government officials worried about feeding men on the battlefield.

Herbert Hoover, then head of the U.S. Food Administration, turned to housewives for help. Pushing the slogan “food will win the war,” Hoover encouraged women to preserve food, eliminate waste and substitute other ingredients for scarce items such as wheat. Mina collected a bursting scrapbook of materials on how to contribute to the war effort through food preservation at home. She taped Woodrow Wilson’s 1917 war message to Congress at the front of the book and stuffed its pockets with canning instructions, pamphlets about supply shortages, and a host of meatless and wheatless menu options.

Wartime food conservation made an impression on Mina. In 1928, she joined Hoover’s presidential campaign, citing his “trust in the womanhood of America” during wartime. The war had strengthened her conviction that domestic interests were national interests. Her home was a public resource.

By the early 1930s, Mina had become a domestic philosopher. Much had changed in women’s work since World War I. It spooked Mina that more and more women were opting to work outside the home. (According to the Brookings Institution, almost 50 percent of single women and nearly 12 percent of married women participated in the labor force in 1930.) She worried these individuals were “victims of a mechanical age” and that “the combination of woman’s suffrage and the war” had given them a distaste for housework. “Unless the women of America make a decided effort to return to the business of home-making,” Mina said in a July 7, 1930, speech, “the most vital foundation of our national life is threatened.” She believed everyone would lose opportunities for cultural development if women did not use their leisure time (extended by labor-saving technologies) to educate themselves and their children.

Mina was conspicuously drawing on what she had learned from 19th-century discourses of domestic economy. Her claims that the home should be a protected, woman-run center for education and social stability could have come straight out of the 1840s. But she added a corporate twist. She rejected the term “housewife.” “As head of the house,” Mina asserted, “woman occupies a most important and enviable position. … ‘Home-executive’ is the title I like to apply to home-makers. The term ‘housewife’ does not apply to the capable woman who conducts her home just as efficiently as the man who carries on his work.”

The ideal household was a complex corporate entity, staffed by “home assistants” (servants) whose duties and pay would be based on skill and training. The home executive occupied a supervisory role like that of a factory foreman. Her position required a stunning array of skills: “She must have executive ability. She must be a good purchasing agent. … She must be something of a chemist … an economist. … She should be versed in music, in art, in literature.” The home executive was an intellectual, a scientist, a businesswoman, an artist and a teacher all in one.

Mina’s goal was to keep the home—and women—central in modern society. Building on the home economists who came before her, she sought to define women’s work as work rather than a vague, idealized calling.

This is not to idealize Mina herself, nor to claim her as a modern feminist. Mina could not leave behind her 19th-century upbringing, nor the idea that the home was women’s domain. And her vision of the executive-run home was only attainable for women with significant financial resources. Even as she updated her vocabulary, she held onto certain dated models of labor, in keeping with the fact that she had live-in domestic servants well into the 20th century. As the much younger Eleanor Roosevelt pointed out in a speech given the same day as Mina’s, many people were now living in modern apartments, and “the woman who sits at home is apt to be idle and not very contented.”

No matter how often she told the press that women belonged in the home, Mina was too practical to place service to a cultural ideal over the demands of day-to-day reality. Indeed, buried within Mina’s more conservative statements were two practical—but radical—suggestions. First, Mina argued that if a family only had enough money to send one child to college, it should be the daughter (the future home executive) and not the son. Second, she acknowledged women’s “desire for financial independence” and believed the husband and wife should split the family income 50-50. Domestic work should be compensated, with the home executive formally recognized as her husband’s “partner and companion.”

“Partner and companion” was exactly what Mina was to Thomas. Glenmont and the laboratory, less than a mile apart, were never separate spheres. Before they had been married a month, Thomas had Mina taking lab notes. During World War I, the Navy worried Thomas wouldn’t join its Consulting Board because Mina thought it was a bad idea. Mina kept tabs on Thomas’ endeavors, from ore milling to phonographs, and helped her sons navigate the family business.

Thomas wasn’t against getting involved in domestic matters, either. In 1903, when Mina threw a Halloween party to benefit her church, guests were greeted by festive elements that bore her husband’s signature: glittering incandescent lights, illuminated placards and a “ghost chamber” equipped with an electrified handrail that shocked unsuspecting visitors. The Edisons, in youngest son Theodore’s words, were a family of “inveterate practical jokers.” These jokers were also thinkers, and they would spend evenings together in the Glenmont living room, looking up references for Thomas’ scientific research.

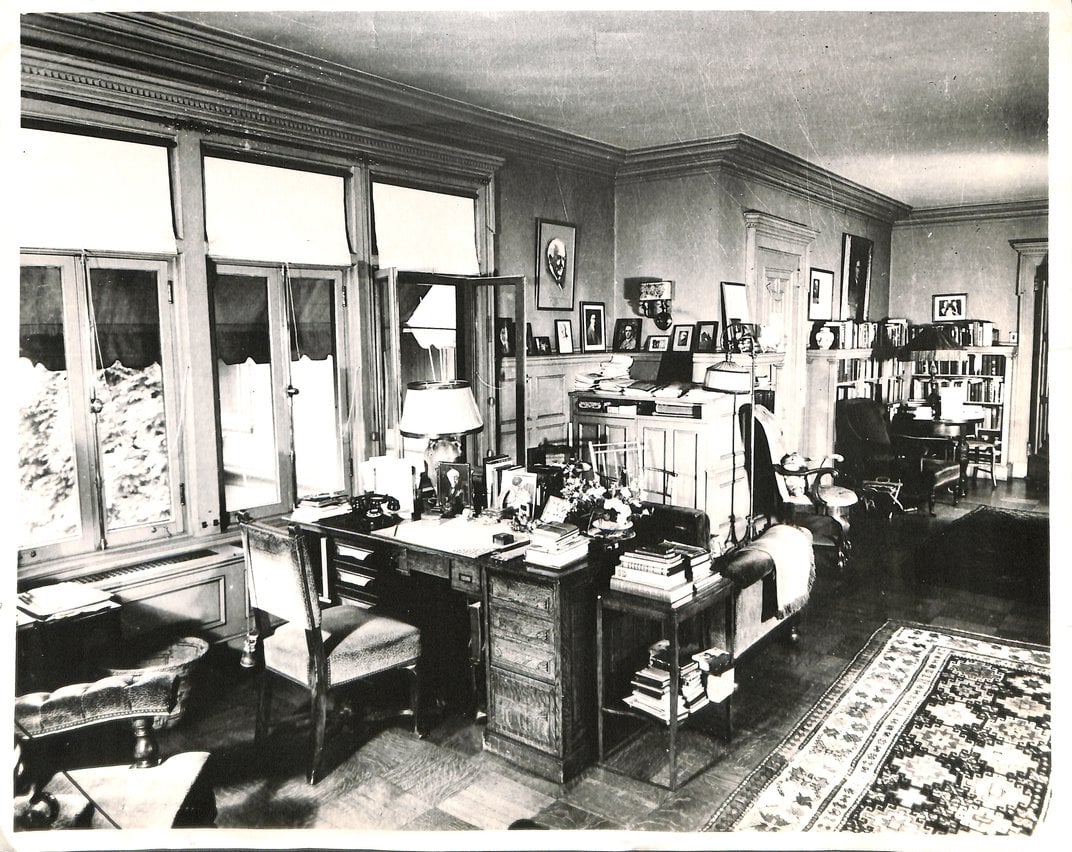

Two large desks dominate this room in the estate-turned-national park—one for Thomas and one for Mina. Here, she could write correspondence; go over accounts; and make plans for the National Recreation Association, the Woman’s Exchange of the Oranges, the National Audubon Society and other organizations to which she lent her talents. Drawers are stuffed with blank stationery. A sliding compartment holds cards for her professional contacts, from taxidermists to travel agencies. Another drawer is full of eyeglasses. Personal mementoes and notes from Thomas are tucked among appointment books and writing implements. Home, family and career are intertwined.

Mina was not ahead of her time. She didn’t leave behind a legacy of radical politics or open protest against gendered restrictions. But that is precisely why she is important to understanding the history of women’s work. Eminently of her time, and poised between eras, Mina was always looking backward and forward, adapting her inherited knowledge to new situations. This history, unfolding in individual lives, is just as political as the history of any large-scale movement. It shows how viewpoints gradually shift, and how the moderate beliefs and daily practices of the late 19th century almost imperceptibly blended into the practices of postwar America. “What goes on in the homes of a nation,” concluded a Washington Post reporter writing about Mina in 1930, “is really more important than what its legislature does, or what its scientists discover.”