On a fall night in 1957, two travelers stopped at a Howard Johnson’s restaurant near Dover, Delaware, for a roadside break. But they were rebuffed, told to take their beverages outside because Black people were not allowed to dine inside. As the men walked out in protest, leaving their drinks on the counter, one made a promise: “You can keep the orange juice and the change, but this is not the last you have heard of this.”

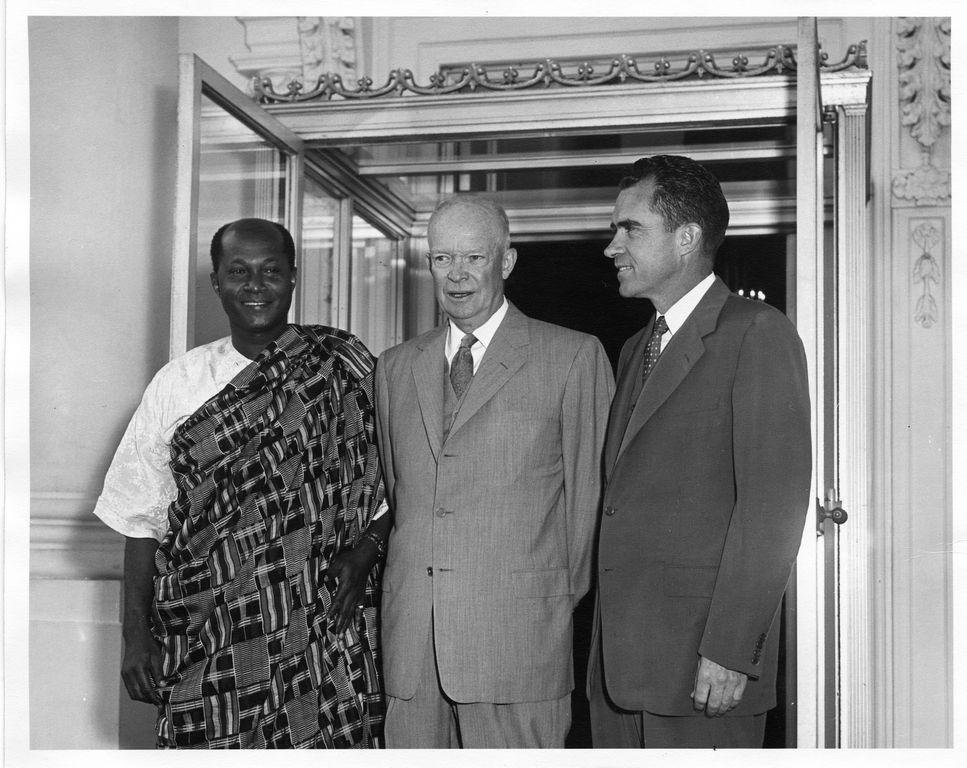

That man was Ghana’s finance minister, Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, who had hosted Vice President Richard Nixon in his home just a few months earlier, when the African country celebrated its independence from Britain. “If the vice president of the U.S. can have a meal in my house when he is in Ghana, then I cannot understand why I must receive this treatment at a roadside restaurant in America,” Gbedemah said at the time.

State Department officials scrambled to publicly apologize for this “exceptional and isolated incident.” On October 10, President Dwight D. Eisenhower invited Gbedemah to breakfast at the White House to make amends; according to Time magazine, Gbedemah expressed hope—at least publicly—that “the people of Ghana understand that there are very few people in the U.S. who act that way.”

Gbedemah’s 1957 meeting with the president was a portent of greater challenges for Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, who was elected in 1960, the year 17 African nations declared their independence from colonial rule. As these countries established diplomatic missions in Washington, D.C., their representatives witnessed the racism directed at Black Americans firsthand—experiences that fueled growing calls for comprehensive civil rights reform in the United States. Kennedy, whose campaign had focused on neutralizing the threat posed by the Soviet Union, found himself forced to contend with a new, rapidly changing foreign policy playing field.

“With the end of formal empire, it means that there are many more world players out there,” says Renee Romano, a historian at Oberlin College. “American foreign policy in Africa had largely been dealing with [European imperial powers] … but now, it’s a very different story in terms of who you need to talk to. And [the United States is] very worried about these new countries becoming communist and then bringing others with them.”

Concerns over adversaries using domestic racial issues as a cudgel had been brewing among American officials for years. In 1947, a committee convened by President Harry S. Truman released a report discussing segregation’s negative effect on America’s international reputation. “The shamefulness and absurdity of Washington’s treatment of Negro Americans is highlighted by the presence of many dark-skinned foreign visitors” who are rejected from establishments in the nation’s capital, the committee argued. Observing a peculiar dissonance of segregation, the group added, “Once it is established that they are not Americans, they are accommodated.”

Truman attempted to address these issues during his time in office, in part by desegregating the Armed Forces with an executive order in 1948. His Justice Department also took the unusual step of filing amicus curiae (Latin for “friend of the court”) briefs in civil rights cases, most notably for Brown v. Board of Education. The president was aware of global attention to America’s racial problems, admonishing in a 1948 message to Congress that “if we wish to inspire the peoples of the world whose freedom is in jeopardy … we must correct the remaining imperfections in our practice of democracy.”

Truman’s successor, Eisenhower, presided over the turbulent implementation of the Brown ruling, sending troops to break up angry mobs in Little Rock, Arkansas, in September 1957. In an address to the nation, Eisenhower lamented how racism in America played into the hands of communists, saying, “Our enemies are gloating over this incident and using it everywhere to misrepresent our whole nation.”

A few weeks after this speech, Eisenhower publicly apologized to Gbedemah at the White House.

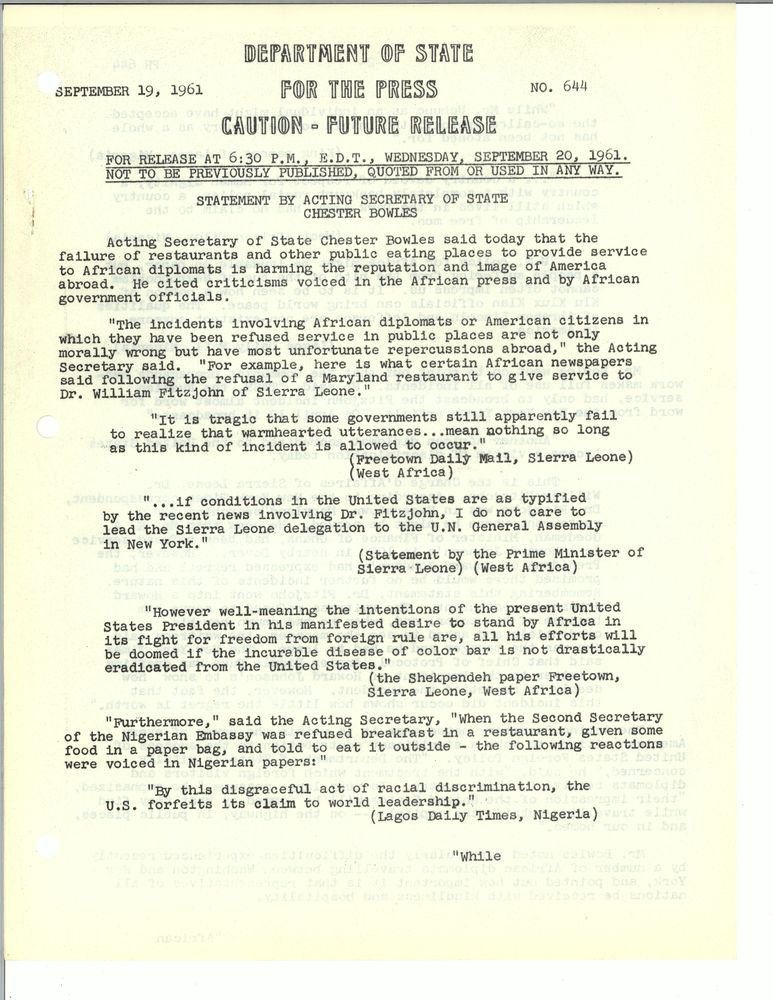

Soon after taking office in January 1961, Kennedy began making similarly high-profile apologies. In March, diplomat William Fitzjohn of Sierra Leone was refused service at a Howard Johnson’s in Maryland. The State Department issued an apology, and the president wrote a letter to seven governors on the Eastern Seaboard, requesting that “foreign diplomats receive friendly, proper treatment while living, working or traveling in their states,” the Associated Press reported.

Polite requests like Kennedy’s had little effect. In June, the owner of a diner outside of Edgewood, Maryland, refused to serve Chadian Ambassador Adam Malick Sow, even after an interpreter identified him as a diplomat. The woman later defended herself to the press, invoking a racial slur in her response: “He looked like just an ordinary, run-of-the-mill nigger to me. I couldn’t tell he was an ambassador.” Her family’s life savings were in the restaurant, she told Life magazine, and business relied on the patronage of “Southern truck drivers” traveling on Route 40, the main highway from Washington, D.C. to New York at the time.

When Sow told Kennedy about the encounter during their first official meeting, the president “got very angry” and asked whether the incident was a “mistake,” aide Pedro Sanjuan later recalled. When Sanjuan emphasized that this treatment was commonplace, Kennedy directed him to meet with the governor of Maryland to “end all this business.”

The sheer number—and visibility—of embarrassing incidents involving diplomats prompted the formation of a new unit within the State Department in March 1961. Dubbed the Special Protocol Service Section (SPSS), this newly created entity was spearheaded by Sanjuan, a Cuban-born staffer who had helped Kennedy campaign in New York City. To kick-start its efforts, the SPSS tackled the two most pressing problems for these foreign visitors: finding housing in Washington and traveling on the roads connecting the capital to their other place of work, the United Nations in New York.

Sanjuan relied in part on the records of Washington Post writer Milton Viorst, who had previously reported on the “kind of treatment that makes assignment to a Washington embassy a hardship for the diplomats of the African nations.” Reading about the discrimination experienced by these individuals “really got me fired up,” Sanjuan remembered.

Despite his relatively junior status and the fact that the SPSS was a nascent organization, Sanjuan felt emboldened by the president’s support, which he invoked both in pressuring business owners and courting the media’s attention. Kennedy himself took a more conciliatory—and sometimes avoidant—approach to civil rights issues early in his term. It would prove untenable, necessitating bolder action near the end of his presidency.

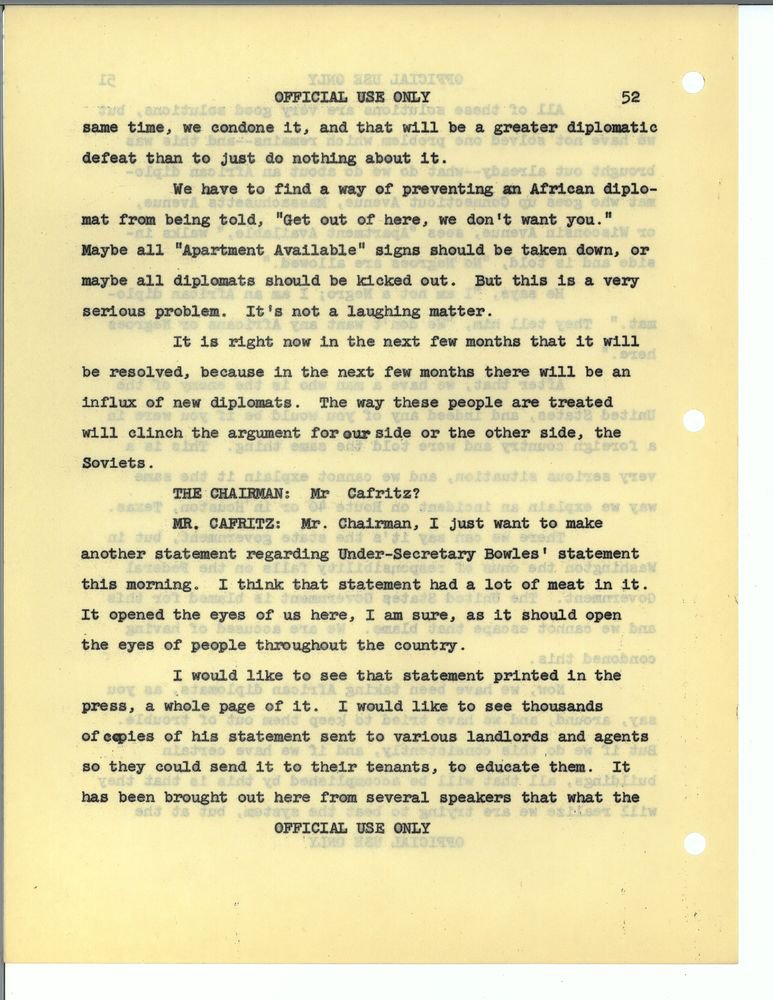

Kennedy’s seemingly simple directive to “end all this business” ran into roadblocks immediately. Meeting with Washington housing officials in the summer of 1961, Sanjuan pointed out that out of more than 200 buildings surveyed in the vicinity of embassies in the city, only 8 would definitely allow African diplomats to rent units. (Amid an increase in the city’s Black population, segregation—both formal and informal—persisted in the nation’s capital.) Considering the “influx” of arrivals expected in the months ahead, he predicted that “the way these people are treated will clinch the argument for our side or the other side, the Soviets.”

Sanjuan’s statement captured the reasoning the SPSS used to target the system of segregation: invoking Cold War patriotism to defend the State Department’s unusual engagement in a domestic problem. The Soviet Union relished opportunities to highlight segregation to hurt America’s image, especially among young nations whose allegiance was up for grabs.

In a September 1961 press release, the State Department highlighted African media outlets’ coverage of Fitzjohn’s treatment in the U.S. One Sierra Leone newspaper called Kennedy’s efforts to support freedom in Africa “doomed if the incurable disease of color bar is not drastically eradicated from the United States.” Another in Nigeria proclaimed that “by this disgraceful act of racial discrimination, the U.S. forfeits its claim to world leadership.” The Soviet Union, despite its frequent reliance on falsehoods in other propaganda campaigns, could in this instance largely parrot domestic newspaper coverage of the incident to embarrass the U.S.

Initial efforts—even those backed by the president—were predicated on persuasion, not compulsion. Sanjuan reminded Maryland legislators that the nations these diplomats represented were “part of a considerable and influential uncommitted bloc” in the U.N. He appealed to “every loyal American in the state of Maryland,” suggesting that “when an American citizen humiliates a foreign representative or another American citizen for racial reasons, the results can be just as damaging to his country as the passing of secret information to the enemy.”

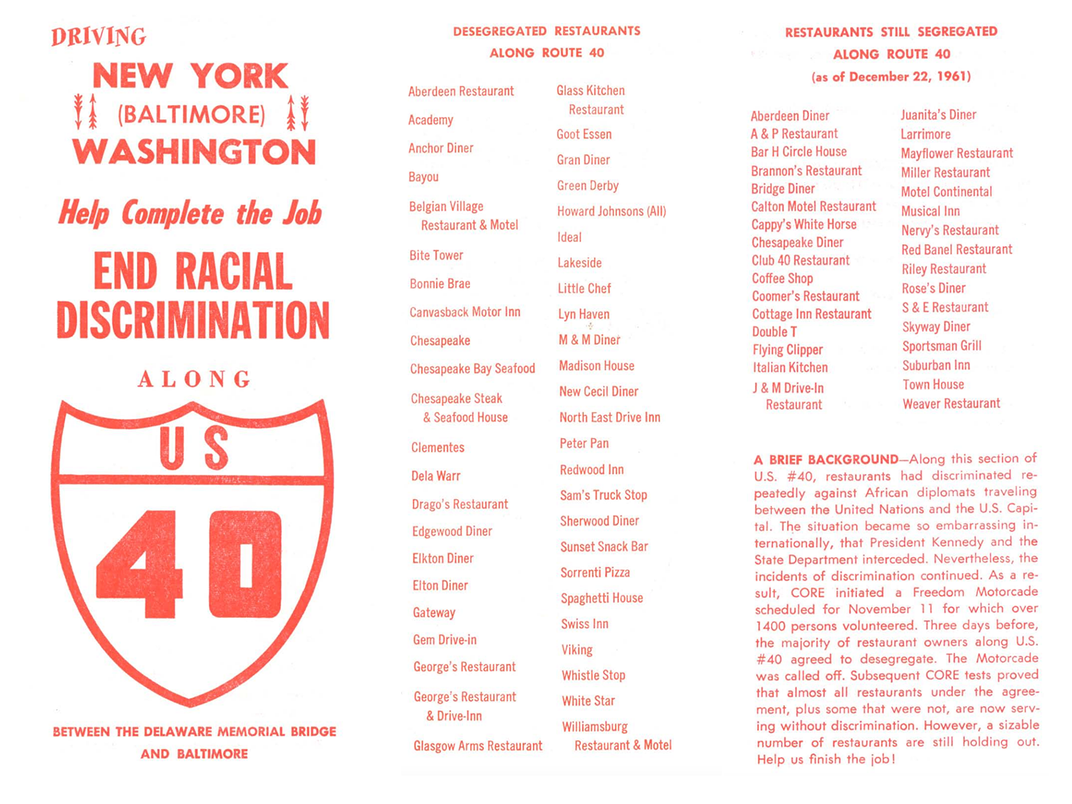

The SPSS’s reason for targeting Maryland was the state’s central location along Route 40. Sanjuan launched a campaign to pressure roadside businesses into compliance, bringing national newsmagazine reporters with him when he showed up to negotiate with restaurant owners—a move that generated both publicity and resentment. One proprietor told Sanjuan off for coming in “with your clean shirt and pressed pants and [telling] me how to run my business.” Others offered no more enthusiasm for the president backing Sanjuan; a restaurateur summarized the perceived intrusion by simply saying, “Let Kennedy feed them if he wants to. I can’t afford it.”

Building on the increased scrutiny aimed at Route 40, members of the Congress of Racial Equality, better known as CORE, began planning Freedom Rides—modeled on bus rides in the South that were then garnering national attention—along the highway in November 1961. Since it wasn’t expressly prohibited by law, restaurant owners could easily discriminate against Black patrons (or those protesting with them) by invoking trespassing laws to force them out. The large-scale rides were called off after dozens of restaurants owners informally consented to desegregation, but protesters kept the pressure on, conducting tests of where the agreement was working and where it wasn’t. Reporters from the Baltimore Afro-American conducted their own experiment, donning seemingly “foreign” attire and claiming to be from the fictitious nation of Goban. Three restaurants served them on the assumption they weren’t American, but two others turned them away

The same irony evident in the Truman committee’s 1947 report held true more than a decade and two presidents later. As Dean Rusk, who served as secretary of state from 1961 to 1969, recalled, “We rapidly discovered that you could not make serious headway on this problem unless there was general headway on the problem of discrimination throughout the city. … You could not expect an African diplomat to carry his passport around with him at all times to find a place to eat.”

The Kennedy administration increasingly found that tailored, one-off solutions to discrimination against diplomats could not mitigate segregation so long as the practice continued to permeate all facets of daily life. The SPSS simply couldn’t shield diplomats from it, whether by appealing to or cajoling business owners, landlords and the ordinary citizens with whom diplomats interacted in Washington and surrounding areas.

Sanjuan’s feedback to the government, says Romano, the Oberlin historian, was essentially that “the model that you’ve given me here is a model set to fail, and that model is essentially moral suasion and deal with these guys on a one-on-one basis to solve the problem.” The historian adds, “It doesn’t work to assuage the diplomats, and it doesn’t work to actually solve the problem or prevent these incidents from happening.”

Efforts toward legal—in other words, enforceable—change moved slowly. It wasn’t until December 31, 1963, that Washington passed a fair housing regulation. When a similar ban on housing discrimination was passed in Maryland in 1963 after being defeated numerous times in the legislature, it applied only to certain counties and didn’t go into effect until June 1964, a short time before federal legislation negated the need for it.

The acceleration of domestic protests sparked progress in the realm of civil rights. Shocking images of violent attacks on protesters in Alabama in the spring of 1963 appalled many Americans and elicited outrage around the world. Once again, the White House was well aware of the detrimental effect these events had when viewed through the Cold War lens. Internal memoranda to Kennedy carefully measured and outlined Soviet propaganda, as well as reactions in other countries. The president addressed the nation on June 11, 1963, calling for national legislation that was broad in scope to address persistent inequalities. This proposal would evolve into the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

By outlawing racial segregation in public accommodations, the federal law both built upon and obviated the need for measures like those passed in Washington and Maryland the previous year. Among those who testified in favor of the act was Rusk, whose words drew heavily from the experiences of the previous two years: “We cannot expect the friendship and respect of nonwhite nations if we humiliate their representatives.”

The African independence movement and Cold War foreign policy mixed in a potent way during Kennedy’s short time in office. But the Civil Rights Act itself was a milestone the president didn’t live to see. It was pending in Congress when he was assassinated that fall.

Much changed in the seven years between Gbedemah’s visit to Eisenhower’s White House in 1957 and the enactment of the Civil Rights Act in July 1964. As President Lyndon B. Johnson remarked after signing the landmark legislation into law, “We believe that all men are entitled to the blessings of liberty. Yet millions are being deprived of those blessings. Not because of their own failures, but because of the color of their skin. The reasons are deeply embedded in history and tradition and the nature of man. We can understand without rancor or hatred how this all happened, but it cannot continue.”