A Brief History of the Erie Canal

The waterway opened up the heartland to trade, transforming small hamlets into industrial centers

Former President Thomas Jefferson considered the proposal “little short of madness.” The project became known as “Clinton’s Folly”—an embarrassment to the state of New York and its governor, DeWitt Clinton. Yet shortly after the locks opened in 1825, completing a man-made waterway that connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, the critics were silenced, and the Erie Canal, one of the greatest engineering marvels in history, charted America’s course from colonial start-up to global superpower.

Around 1807, commercial interests in New York State started agitating for a canal to link the Midwest and the Eastern Seaboard. A transportation corridor to the Great Lakes would open the nation’s interior to global trade and promote the development of an American heartland. Raw materials would come east; people would move west. In Clinton’s hopeful words at the canal’s opening ceremony: “The most fertile and extensive regions of America will avail themselves of its facilities for a market … [and New York City] will, in the course of time, become the granary of the world, the emporium of commerce, the seat of manufactures, the focus of great moneyed operations.”

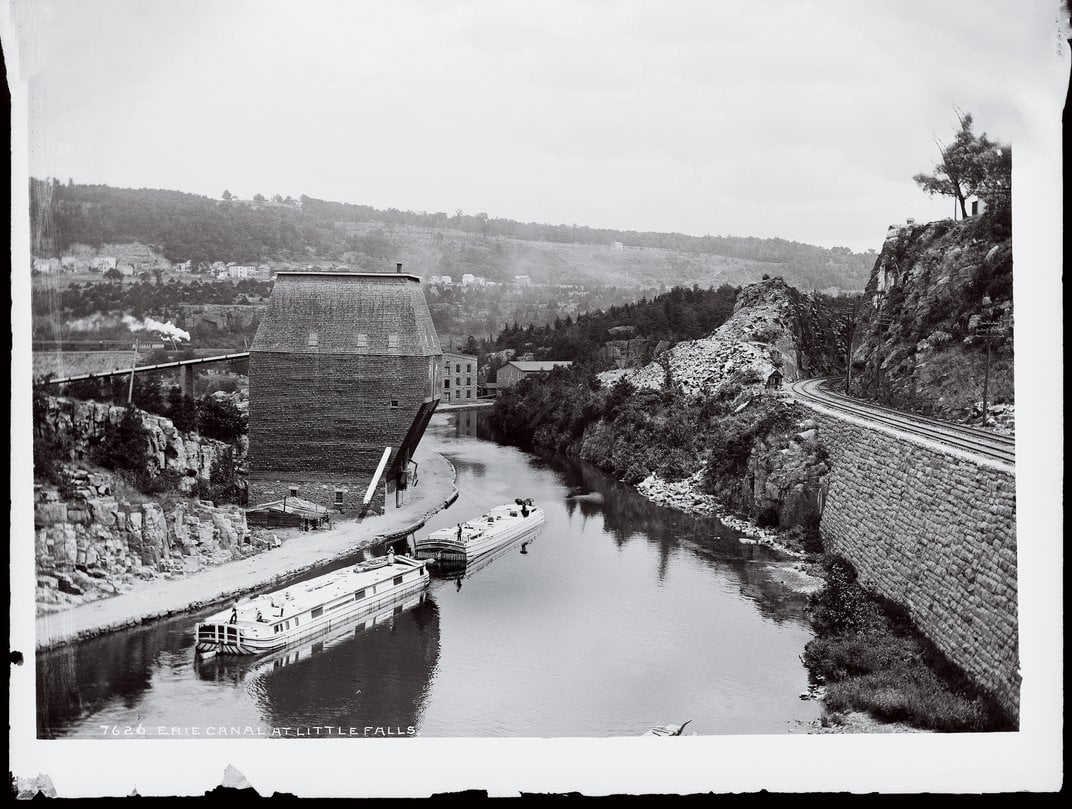

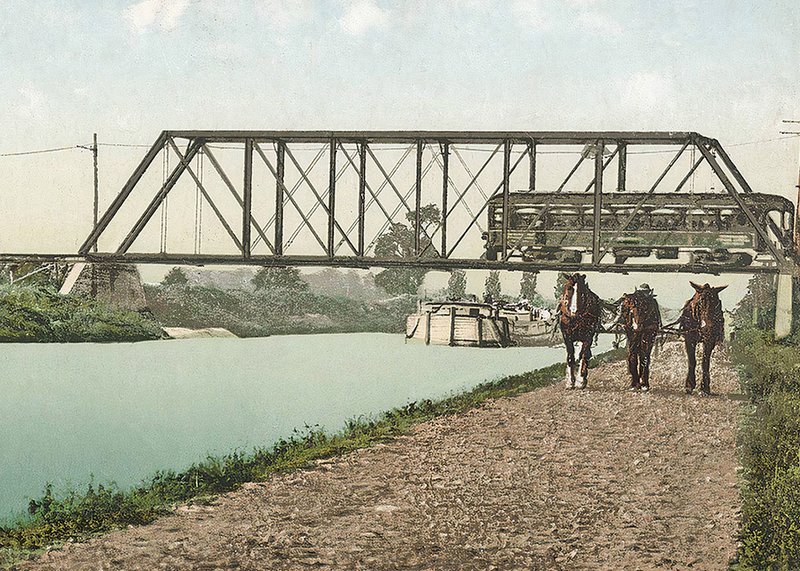

Easier said than done. America had few civil engineers. Equipment was crude. William Otis wouldn’t patent his industrial steam shovel until 1839, and Alfred Nobel’s dynamite wouldn’t appear until 1866. Muscle would build the canal. Construction began in 1817, and soon Benjamin Wright, a prominent surveyor, became chief engineer. Clinton’s doubters were correct that the engineering challenges were unprecedented. Wright’s roughly 9,000 laborers channeled nobly through impossible rock formations. Sometimes they’d crack the stone with gunpowder, a volatile and deadly option; other times, they would use a drill bit invented for the task. To dig the canal trench—4 feet deep, 40 feet wide, running 363 miles from Albany to Buffalo—the men used picks and shovels. There were intense risks: Malaria, mysterious illnesses and grisly construction accidents disabled hundreds of workers, killing many.

Some workers found the territory irredeemably harsh: “The land is a desolate wilderness,” William Thomas, a Welshman who had come to work on the canal in 1818, wrote to his family back home. “I beg all of my old neighbors not to think of coming here.”

The greatest challenge was elevation: Lake Erie, the canal’s western terminus, is more than 570 feet above sea level. The Hudson River at Waterford, New York, the eastern terminus, is a mere 16.5 feet in elevation. Given rises and dips along the way, the engineers knew the canal couldn’t be a continuous river. It would have to be arranged in a series of waterways, each occupying its own elevation, with those strips connected by locks—great concrete bathtubs, designs for which Wright and other engineers copied from the finest English and French canal builders of the day: A boat floats in, the doors close, and piped water flows into or out of the sealed chamber, raising or lowering the water level so the vessel can float on to the next stretch. Once complete, it would be one of the longest canals in the world.

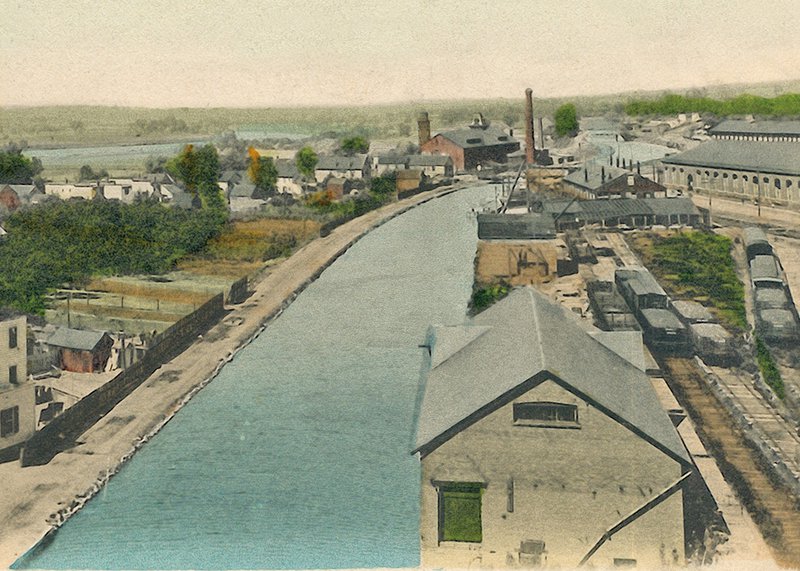

After the canal opened, in October 1825, economic gains were swift and helped transform New York City (roughly 150 miles down the Hudson from Waterford) into the nation’s premier seaport, surpassing Philadelphia and Boston. The canal corridor also served as an important route on the Underground Railroad: Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass lived nearby, providing refuge to those in flight. The canal wasn’t just an engineering feat; it was a community linked by water, and by the belief in a better tomorrow. The 1912 song “Low Bridge, Everybody Down,” perhaps better known as “Fifteen Miles on the Erie Canal,” offered the country a nostalgic vision of plucky life on the barges and a celebration of the booming canal cities that helped turn New York into the Empire State.

But perhaps the greatest marvel today is that the canal is still in vibrant use, its machinery largely remaining in continuous operation. While freight rail and the St. Lawrence Seaway have made the canal’s commercial traffic mostly obsolete, despite the occasional tugboat pulling a barge, it is frequently traversed by anglers or Great Loopers—recreational boaters who circumnavigate the Eastern Seaboard via the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico and back up along the Atlantic. “A lot of people look at [the canal] as history,” says Paul Guarnieri, chief lock operator at Waterford E-2. “But we’re still here.” The canal remains a playground and a testament to American engineering—at once a call to adventure and a gentle edict to slow down and unplug: “Life in the slow lane” is the canaller’s motto today; along several stretches, the motorized speed limit is a mere five miles per hour.

What do we do with glorious things that have outlived their original intent? When we’re wise, we preserve them. When we’re brilliant, we preserve and repurpose them. As you watch these spirited modern-day canallers making these waters their own, the venerable canal still seems to embody hope for the future.

Boom Time

How the Erie Canal transformed quiet rural villages into thriving commercial cities

Buffalo

Rochester

Syracuse

Schenectady