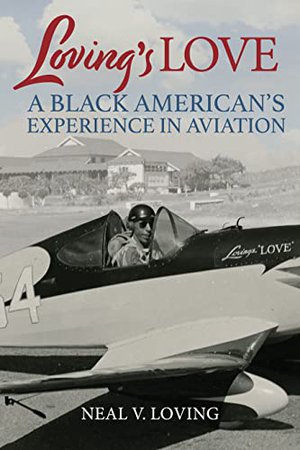

In 1946, a Black Pilot Returned to the Cockpit After a Double Amputation

Neal V. Loving, whose memoir will soon be released by Smithsonian Books, built his own planes, ran a flight school and conducted research for the Air Force

Born in Detroit in 1916, Neal V. Loving discovered his passion for aviation at a young age, eagerly following Charles Lindbergh’s solo, nonstop trans-Atlantic flight in May 1927. Loving dreamed of becoming a military pilot but shifted focus to aeronautics engineering after discovering the Army Air Corps did not accept Black aviators. In 1936, he constructed his own glider, and in 1938, under the guidance of a private instructor who had previously taught Michigan’s first licensed Black private pilot, he flew a plane for the first time.

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Loving helped found an all-Black squadron of the Civil Air Patrol, a volunteer training program for young pilots. In this excerpt from his 1994 memoir, Loving’s Love: A Black American’s Experience in Aviation, to be rereleased by Smithsonian Books next week, the aviator and engineer recounts the wartime accident that led to his double amputation.

On Sunday, July 30, 1944, I took off on what should have been a routine training mission for the Civil Air Patrol. It ended in a disastrous crash, excruciating pain and instant unconsciousness.

When I awoke, I looked at my feet, which should have been pointing upward, and found they had twisted 90 degrees. With my left eye, I could see my right eye had come out of its socket and was lying on my cheekbone. Blood was streaming profusely from a severe cut just above my eyes, extending across my entire forehead.

Loving’s Love: A Black American’s Experience in Aviation

The uplifting autobiography of a remarkable aviator who was the first African American and first double amputee licensed as a racing pilot

After what seemed to be an interminable delay, a medical truck arrived in response to the emergency call, and I was quickly loaded onto a stretcher and taken to St. Joseph Hospital in Mount Clemens, Michigan, nine miles away. The driver sped over the rough country roads as fast as possible, causing my broken legs to bounce uncontrollably.

As we drove up to the hospital emergency entrance, we were met by a large medical team that was prepared to treat numerous survivors of the reported crash of a huge Army transport airplane. Evidently, when the alert came in, the caller described the large number of people in Army Air Forces uniform at the scene of the accident and assumed many were injured. Every available doctor and nurse had reported to the hospital for immediate duty. I don’t know if they were disappointed with having just one scrawny, 135-pound patient, but I was lucky to have both the head surgeon and the head nurse on hand.

After surgery, I was heavily sedated and had little sense of pain. My right leg was elevated in traction. A surgical pin in my heel was attached to a wire that ran over a pulley mounted on the bedstead to a lead weight. I couldn’t see my left leg lying flat on the bed, but it felt normal, with the exception of a slight tingling sensation. It was only later that I learned the doctors had amputated my left leg.

When I woke up one afternoon during visiting hours, the first person I recognized was my mother. She spoke as soon as my eyes opened, her voice filled with sadness: “Neal, I am so sorry you have lost your leg.” Still unaware of the amputation, I made a feeble attempt to humor her, responding, “Mother, you must be in the wrong room.” Realizing she was the first to inform me, she changed the subject and talked of more pleasant matters.

When a patient loses a limb, there is no immediate, innate sense of physical loss. The nerves leading from the stump to the brain continue to send normal messages. Only when the stump becomes visible does the patient realize the loss. During this period of waiting, no one brought up the subject of my amputation, other than my mother (I did not believe her at the time), and it became quite a game between my nurses and visitors to determine when I would make the discovery.

I don’t remember the moment when I found out. But I did not experience the outward trauma the doctors had predicted. Inwardly, I was deeply disturbed not only by the amputation but by the negative effect it would have on my career as a pilot. There were times of quiet despair, often difficult and sometimes impossible to overcome. But I kept these feelings to myself. I did not discuss them with anyone, especially the possibility I might never pilot an airplane again.

One of the early visitors to my hospital room was a slightly overweight young salesman from a local artificial limb company. He had read the account of my accident in the newspaper and noted that one of my legs had been amputated. He was out of breath as he greeted me. I invited him to sit down. He had climbed three floors to reach my room without realizing an elevator was available. When I teased him about his weight being a factor, he laughed and said the real problem was he had one artificial limb.

What an inspirational surprise that was. This was far more convincing proof than assurances from hospital staff. He showed me his prosthesis and gave a sales talk. I poured out my questions: Would I drive a car again or climb a ladder? I was afraid to ask if I might fly again. Assuring me I could live a reasonably normal life with his company’s prostheses, he gave me his business card and renewed confidence in the future. I promised to contact him when I left the hospital.

The salesman’s visit reinforced the hope I had developed from reading about the exploits of Douglas Bader, a legendary combat fighter pilot who served during World War II after undergoing a double amputation. Bader continued to be my role model and inspiration whenever I started dreaming of flying again.

One morning in early December 1944, I woke to a wonderful surprise: The constant pain I had endured for months had all but disappeared. I couldn’t wait to tell the good news to my doctor and congratulate him on his surgical skills.

When he came to my room for his morning visit, I was surprised by the glum expression on his face. I decided to cheer him up by telling him how successful my most recent operation had been and my new relief from pain. He listened patiently, then told me the bad news. During the operation, while he was scraping debris from around the ankle joint, my shin bone fractured completely. The only choice was to remove the broken bone. Now, the only connection between my foot and ankle was cartilage and tissue. This was also the reason for the lack of pain, which had been caused by friction between the fractured bones. The only reasonable solution, he explained, was to amputate my right leg.

My doctor discussed all the possibilities and suggested I send the X-rays of my foot to experts of my choice for a second opinion. To raise my sagging spirits, he offered to let me go home for Christmas. This, he hoped, would increase my appetite, for I had been steadily losing both weight and strength. There would be considerable risk involved in the amputation. He wanted me to be at my best both mentally and physically. He estimated I had a 50-50 chance of survival.

Despite my many misgivings, the operation was a medical success. It was now necessary that I start preparing for my life as a double amputee. The first task was to build up my strength and energy for the long, painful process of learning to walk again. In those days, there were no physical therapy programs designed specifically for amputees. Under the guidance of my doctor and nurses, I tried to get as much exercise as possible both in the wheelchair and by performing in-bed aerobics.

I weighed only 135 pounds when I entered the hospital and could only guess how much weight I had lost in the subsequent six months. But just the thought of returning home and resuming my life was all the incentive I needed.

On Valentine’s Day 1945, I was discharged from the hospital amid numerous farewells and even a few tears, some my own. With promises I would stay in touch and pay a visit to the hospital when fitted with my new legs, I climbed into my Buick and, at long last, was on my way home to stay.

As soon as I could arrange for transportation, I made my first visit to the Fidelity Orthopedic Company, where I met with the salesman who had visited me in the hospital to discuss the purchase of my new prostheses. It was then I discovered one of the few advantages of being a double amputee. After a few preliminary questions, the fitter casually asked me how tall I wanted to be and what size shoe I wanted to wear. Not many people get to make that decision.

Considering the many possibilities, I decided to retain my same height and shoe size so I could continue to use my existing wardrobe. With this important decision out of the way, the fitter wrapped my stumps with wide elastic tape that I was to wear every day for a month. The purpose was to shrink the stumps to their natural size before fitting the prostheses. Then began the long, often very painful process of fitting my new legs, which required about three weeks to complete.

Every day, I walked around the house on my new legs from chair to chair, sometimes leaning on the wall for support or even falling when I lost my balance. Although the pain was very severe, especially when water blisters formed on my legs, I was determined to keep them on all day long. Gradually, I gained strength and skill. Within a few weeks, I was ready to attempt a walk, using crutches, from my house out to the front sidewalk. With neighbors peeking through their windows, I struggled along the walkway for what seemed an enormous distance until I reached the sidewalk. Finally, sitting down in my living room chair, exhausted from my efforts, I felt my first baby steps had been completed and I was on my way to independence.

The news of my progress must have reached Detroit City Airport, because Telford “Dunc” Duncan, who owned a flight training school there, soon called and asked if I was interested in coming out for a visit. “Would an alcoholic like to have another martini?” I asked. That must have answered his question, for he was knocking on my door just as I finished changing clothes.

Duncan drove me around the huge hangar so I could see all the latest airplanes, then out to the flight line, where the sounds of engines and propellers were music to my ears. I was content to just sit there and drink in the atmosphere that had only been a memory for the past eight months.

The strain of walking on my new legs soon caused my newly healed stumps to swell, resulting in pain that even the joy of being at the airport could not alleviate. With reluctance, I asked Duncan to drive me home, where, upon arriving, I immediately and uncharacteristically took my legs off to ease the pain. Sitting in my living room chair and thinking about my airport visit, I realized my love of aviation was undiminished. But I still did not know if mental trauma from my accident might cause me to have an uncontrollable fear of flying. The answer could only be determined in the air. With mixed emotions, I asked Duncan to take me flying as soon as possible.

On my next visit to the airport, I climbed awkwardly into the front seat of a plane, fastened my safety belt and performed a cockpit check. After looking at the familiar dials on the instrument panel, I was soon relaxed and impatient to be airborne. Duncan climbed in the back seat and closed the door. We went through the routine engine start procedures and called the familiar word “contact” to the waiting mechanic. The craft’s engine came quickly to life, its vibrations shuddering through the fuselage. The tower called, “Aeronca 426, you are cleared for takeoff, runway 33.” Pushing the throttle forward, I felt the familiar surge of movement and excitement as we raced down the runway. My eyes followed the airplane’s dancing shadow moving along the ground, growing smaller as we continued our climb. The unbounded freedom of the sky I had been dreaming of for months was now a reality as we cruised in joyful flight above green farmlands.

Upon arriving in the practice area, we went through basic turns and orientation maneuvers to test my coordination between hand pressure on the control stick and forces I needed to apply to the rudder pedals with my artificial legs and feet. After some initial awkwardness, I was soon performing all the maneuvers with confidence and skill.

Encouraged by my performance, we flew over Wings Airport, near Detroit, for the crucial test. Starting at as low an altitude as feasible, I entered a 180-degree turn followed by a stall entry and spin, the same sequence of events that led to my accident. The ground rushed toward me, spinning in a familiar blur of green and brown. I recovered quickly and returned to level flight. Duncan leaned forward and patted me on the back. I smiled in return, happy in the realization that the fears or emotional scars that might destroy my love of flying had not materialized.

After returning to the cockpit, Loving continued his aviation career by launching his own flight school and building experimental racing planes. He earned a degree in aeronautical engineering from Wayne State University in 1961, graduating as the oldest full-time engineering student in the school’s history. Loving spent the next 20 years conducting research for the Air Force, retiring in 1982 and publishing his memoir in 1994. He died in 1998 at age 83. One of Loving’s airplane designs, the WR-3, is on view in the newly reopened West Wing of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Excerpted from Loving’s Love: A Black American’s Experience in Aviation by Neal V. Loving. Published by Smithsonian Books. Copyright © 2023 and 1994. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.