Haiti’s Beloved Soup Joumou Serves Up ‘Freedom in Every Bowl’

Every year, Haitians around the globe eat the pumpkin dish on January 1 to commemorate the liberation of the world’s first free Black republic

Growing up as a Haitian American, January 1 has always been more than just the start of the new year for me. As a child, waking up on New Year’s Day, I practically floated through the air to the aromas of soup joumou, or Haitian pumpkin soup, resting in one of the decorative bowls my mother reserved for the annual tradition.

Every New Year’s Day, Haitians around the world consume soup joumou as a way to commemorate Haitian Independence Day. On January 1, 1804, Haitians declared independence from French colonial rule following the Haitian Revolution that began in 1791. Soup joumou is a savory, orange-tinted soup that typically consists of calabaza squash—a pumpkin-like squash native to the Caribbean—that’s cooked and blended as the soup’s base. To that base, cooks add beef, carrots, cabbage, noodles, potatoes and other fresh vegetables, herbs and spices.

“[Soup joumou] is freedom in every bowl,” says Fred Raphael, a Haitian chef and co-owner of two Haitian restaurants in the New York City metropolitan area. “[Haitians] fought for unity, just the same way we get all these different ingredients that come together and create this taste.”

Haiti, then called Saint-Domingue, formally came under French occupation in 1697 after Spain ceded the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola to France, according to Bertin Louis Jr., a cultural anthropologist at the University of Kentucky. To sustain the island’s colonial economy—which predominantly centered on the production and export of crops like sugar, coffee and tobacco—French plantation owners captured and enslaved nearly 800,000 Africans as a labor source on the island. Saint-Domingue, by the early to mid-18th century, grew to be the most profitable colony in the world.

During the colonial era throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved Africans cultivated squash, the crop at the center of soup joumou. According to Louis, enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue were prohibited from eating soup joumou, despite being the ones who prepared, cooked and served it to white French enslavers and colonizers. The soup was a symbol of status, and by banning enslaved Africans from consuming it, the French were able to assert their superiority, challenge the humanity of Black Africans, uphold white supremacy and exert colonial violence, Louis says.

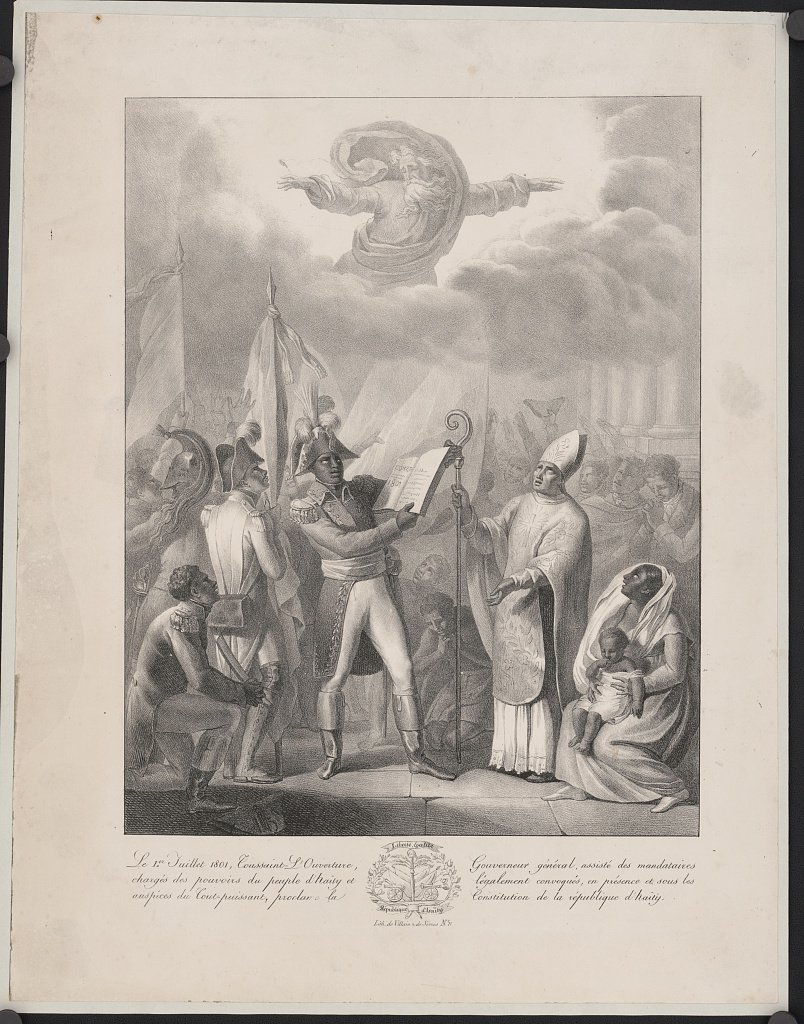

Following the nearly 13-year struggle of the Haitian Revolution led by revolutionaries like Toussaint L’Ouverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, Haitians declared independence from French control and celebrated their liberation by eating soup joumou. It is said that on January 1, 1804, Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines, the first empress of Haiti and Jean-Jacques Dessalines’ wife, distributed the soup to freed Haitians. Over two centuries later, the tradition of eating the decadent soup continues in celebration of a large-scale slave revolt that created the world’s first free Black republic.

“The soup represents the claiming and reconfiguration of a colonial dish into an anti-colonial symbol of resistance and also Black freedom, specifically Haitian freedom,” Louis says.

For chef and restaurateur Raphael, it was a no-brainer to include soup joumou on the menus at both of the restaurants he co-owns—First Republic Lounge and Restaurant in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and Rebèl Restaurant and Bar in New York’s Lower East Side. “You don’t have a Haitian restaurant if you don’t make soup joumou,” he says. In the near-decade since First Republic Lounge and Restaurant opened—Rebèl Restaurant and Bar opened several years later, in 2020—Raphael has made it a tradition to create a space for Haitian and non-Haitian community members to come together and enjoy the dish.

“We make it a practice in both restaurants to give [soup joumou] away for free the night of December 31 as we bring in the new year,” Raphael says. “We usually make a pot of vegetarian soup with no meat, and then there’s another pot with meat, and anyone can come in and enjoy that.”

Combined, the restaurants usually see a turnout of about 300 to 500 guests. Raphael and his colleagues spend days preparing for the event, which begins in the evening of New Year’s Eve and goes until the early morning hours of New Year’s Day. For Raphael, the soup presents an opportunity to educate people and bridge cultural gaps, whether that is non-Haitians trying the soup and learning the history behind it or Haitian Americans who have never been to Haiti or haven’t been back in years feeling more connected to the island. “We make sure that [soup joumou] is served properly, because we want you to see the pride in making this,” Raphael says. “It’s sweat and tears, and a lot of folks have died to ensure that we have the freedom we have today.”

Nadege Fleurimond, a Haitian chef, restaurateur and cookbook author, says soup joumou reminds her of the importance of cultural heritage, family and community. She recalls growing up in Brooklyn, New York, with her dad and helping him prepare the soup, but also visiting the homes of other family members and friends and trying their versions. “There’s a soup that’s made in your house, there’s also people bringing you soup because they’re visiting you, or you may be visiting someone,” says Fleurimond, who owns the Haitian restaurant BunNan in Brooklyn. “Soups vary from family to family, from household to household, but the thing I remember is how this was the day that everyone came together because you wanted to celebrate, you wanted to unite in this legacy of our ancestors.”

When it comes to preparation, Fleurimond says she used to think making soup joumou took days when she was a child. She remembers family members first chopping up vegetables and getting ingredients together. In hindsight, she realizes the process took so long because her family members were making large pots of soup, but also because the communal aspect of the dish went beyond just eating it together. She recalls her aunts in the kitchen talking about everything and nothing as they prepared the soup and cut vegetables. “It was an opportunity to congregate, so things took a little longer,” Fleurimond says. The actual cooking of the soup takes around two hours.

Once the soup is ready, it’s typically eaten as breakfast, lunch and dinner on New Year’s Day and consumed into the next day as part of Ancestors’ Day—a holiday honoring Haitian revolutionaries—on January 2. In the 219 years since Haiti declared independence, soup joumou has gone through various changes, with different families in different regions in Haiti and around the world putting their own twists on the dish. For example, modern versions of the soup typically include pasta like rigatoni or penne, but it’s unlikely that was a core part of the soup back in the 1800s, Raphael says.

With the rise of social media, Fleurimond says people can easily share recipes and pictures of their versions of soup joumou, and she’s seen many online debates about the “right way” to make it. Some people say soup joumou is only soup joumou if it has meat in it—though it’s said the original version was vegetarian. People also argue about the correct pasta and vegetables to put in the soup, but Fleurimond sees the debates as comical and ultimately arbitrary. “Yes, there’s a base, but at the end of the day, [soup joumou] does vary from region to region and household to household, because people use what ingredients they have access to,” she says. For both Fleurimond and Raphael (and myself), the soup is usually paired with a side of Haitian bread, a hard dough bread with a chewy texture, at family gatherings.

Amid ongoing social and political crises in Haiti, Raphael says the message and history behind soup joumou matter more than ever. Historians and scholars have connected many of Haiti’s plights in the decades following its liberation, as well as difficulties faced in recent years, to the fact that foreign powers went on to exploit and drain the island’s wealth for generations after the country overthrew slavery and declared independence in 1804. After Haiti broke free from French rule, its government was forced to pay former French slaveholders and their descendants about $560 million in today’s dollars over the course of 64 years—money that would have amounted to $21 billion if it remained in Haiti’s economy.

Today, Haiti struggles with gang violence, a cholera outbreak, poverty, acute hunger and continued foreign intervention attempts opposed by many Haitians. As a result of these issues, many have immigrated, moved out of and fled the country in recent decades and years, with Haitians now spanning the globe. Fleurimond says soup joumou allows Haitians around the world to come together and celebrate a common history.

“We need a revolution in Haiti right now because of what’s going on in terms of political and social turmoil,” Fleurimond says. “Whenever January 1 comes around, [Haitians] have this one anchor point of the soup. It reminds us of what we’ve done, what’s still possible if we do come together and also that sense of community that’s authentically felt. It’s more than just the household that’s making the soup—it also spreads to everyone in your community making the soup, and every Haitian in the world that is making this soup. This just shows we really are one.”

Nadege Fleurimond’s Soup Joumou Recipe

Serving size: 10-12

Ingredients

For the epis seasoning

- 1/4 medium onion

- 1/2 green bell pepper, chopped

- 1/2 red bell pepper, chopped

- 1/2 yellow bell pepper, chopped

- 10 scallions, chopped

- 12 garlic cloves, chopped

- 1 cup parsley, chopped

- 2 sprigs of thyme (just the leaves)

- 1/4 cup olive or canola oil

For the soup

- 1 cup distilled white vinegar

- 1 whole lime, cut in half

- 2 pounds of beef (mixture of chuck, beef stew, soup bones)

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 cup epis seasoning

- 3 tablespoons fresh lime juice, divided

- 1 tablespoon seasoned salt

- 1 medium calabaza squash (about 2 pounds), peeled and cubed, or 2 pounds defrosted frozen cubed calabaza squash, or 1 butternut squash (about 2 pounds), peeled and cut into 2-inch chunks

- 2 large Idaho potatoes, cut into cubes

- 2 carrots (about 1 pound), sliced

- 1/4 small green cabbage (about 1/2 pound), very thinly sliced

- 1 medium onion, sliced

- 1 celery stalk, coarsely chopped

- 1 leek, white and pale-green parts only, finely chopped

- 2 small turnips, finely chopped

- 1 green Scotch bonnet or habanero

- 6 whole cloves

- 1 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1 teaspoon onion powder

- 2 teaspoons kosher salt

- 1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- A pinch of cayenne pepper

- 1 parsley sprig

- 1 thyme sprig

- 1 cup rigatoni

- 1 tablespoon unsalted butter

Instructions

- Start with making the Haitian epis seasoning by placing all ingredients in a blender or food processor and blending.

- Pour 1 cup vinegar into a large bowl. Swish beef in vinegar. Squeeze lime halves and clean meat the Caribbean way by rubbing the meat with the insides of the lime pieces. Rinse with cold water, strain and set meat aside in large soup pot.

- Add oil, 1 cup of epis seasoning, 2 tablespoons lime juice and seasoned salt to pot with meat. Toss to coat, then let marinade at least 30 minutes, preferably overnight.

- After marinading, bring meat pot to medium heat and add in 2 cups of water. Cover and let simmer for 40 minutes, continuously adding water, until meat is soft.

- In a separate pot, add squash with 4 cups of water. Cook on medium heat until squash is fork tender, about 25 minutes.

- Once cooked, purée squash in a blender or food processor. Add to pot of cooked meat.

- With the soup pot still on medium heat, add an additional 5 cups of water. Add potatoes, carrots, cabbage, onion, celery, leek, turnips, the green Scotch bonnet or habanero pepper, cloves, garlic powder, onion powder, salt, pepper, cayenne, parsley and thyme. Add water as necessary to ensure liquid is at least 2 inches above vegetables and meat.

- Simmer, uncovered, continuing to add water as necessary until vegetables are tender, about 25-30 minutes.

- Add in rigatoni, butter and remaining 1 tablespoon of lime juice. Simmer on low until pasta is cooked, about 10-12 minutes.

- Taste and adjust seasonings as needed.