Thirty-Five Years Later, a First Responder at the Chernobyl Disaster Looks Back

In her new book, Alla Shapiro shares her experience of one of the worst nuclear disasters in history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/ff/5aff653e-f0b7-4496-8583-1a2ed4bd56c4/chernobyl.jpg)

April 26, 1986, started off like any other day for Alla Shapiro. The pediatrician, then 32 years old, was at work in the Pediatric Hematology Unit at the Children’s Hospital in Kiev, Ukraine. But everything changed when she learned that an explosion had occurred 80 miles north at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, just outside the city of Pripyat. In the hours that followed, hundreds of children arrived at the hospital by bus seeking treatment.

As a front-line worker, it was the first time that Shapiro and her colleagues were faced with treating patients during a disaster of Chernobyl's magnitude. Unfortunately, the Soviet government didn’t have any nuclear disaster protocols in place, and basic supplies were severely limited, leaving medical professionals to improvise and adapt. In the days and weeks that followed, Shapiro discovered that the government was misleading the public about its handling of the explosion, which was caused by a flawed reactor design, according to the World Nuclear Association.

The explosion occurred at 1:23 a.m. during a routine maintenance check of the plant's electrical system, when operators went against safety protocols and shut down parts of the control system that were necessary to run the plant safely. The result was an unexpected sudden surge in power due to excess steam building up in one of the reactors. The accident killed two plant workers immediately, but soon dozens more would perish from acute radiation sickness, including emergency workers and firefighters who were sent to the scene. Over the years, thousands of people would succumb to radiation contamination from the explosion, with the number of total deaths unknown since many people died years and decades after the fact. Cancer, particularly thyroid cancer, would become a common link among survivors, including Shapiro, who, now in her late 60s, is a cancer survivor herself. Approximately 20,000 cases of thyroid cancer were registered from 1991 to 2015 in regions affected by the Chernobyl accident, according to a report published by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). The high numbers are due to the fallout from the explosion, with winds carrying toxic particles as far away as Switzerland.

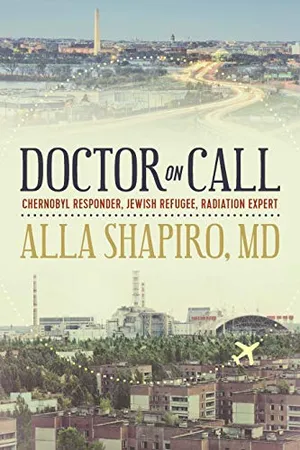

Doctor on Call: Chernobyl Responder, Jewish Refugee, Radiation Expert

Dr. Alla Shapiro was a first physician-responder to the worst nuclear disaster in history: the explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station in Ukraine on April 26, 1986. Information about the explosion was withheld from first responders, who were not given basic supplies, detailed instructions, or protective clothing. Amid an eerie and pervasive silence, Dr. Shapiro treated traumatized children as she tried to protect her family.

On the tragedy’s 35th anniversary, Shapiro shares her story from the frontlines of Chernobyl in a new book called Doctor on Call: Chernobyl Responder, Jewish Refugee, Radiation Expert. In her memoir, Shapiro discusses not only the disaster, but also her experience immigrating to the United States with her extended family and her work as a leading expert at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in developing medical countermeasures against radiation exposure. Her work is a testament to the importance of preparedness, especially in the face of adversity. Even now in retirement, Shapiro continues to work tirelessly in strengthening the preparedness of the United States against nuclear disaster. She's currently a consultant and an advisory board member for Meabco A/S, an international pharmaceutical company, that's developing a novel drug that could potentially protect humans from harmful doses of radiation. She's also conducting webinars for scientists and medical care providers who are interested in the health effects of radiation on humans.

Shapiro spoke with Smithsonian about her personal experience during one of the worst nuclear disasters in history, the Soviet government’s failure to act swiftly and transparently during the catastrophe, and her thoughts on the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic today.

What was going through your head as hundreds of children arrived at your hospital for treatment after the Chernobyl explosion?

I really didn’t have time to get scared or to get prepared. We saw the children arriving in a panic and in tears. It was a stressful event, but you have to act and do what you have to do. The negative thing was that we didn’t have any instruction, knowledge or training in radiation, so we exercised our [medical] background and did what we could. We also didn't have enough supplies and proper protective clothing to wear during examinations.

Since a similar disaster was never recorded in medical history books, and there were no guidelines in place for how to handle the situation, you had to innovate. Can you give an example of how you improvised?

We tried to comfort the children. It was only much later that we learned the psychological impact [of the disaster]. We told them funny stories and hugged them, which worked quite well. And then we looked at what we were facing—if children were coughing, at first we didn’t know why. In pediatrics, if a patient has a cough, most likely a fever will follow, but not in this case. We soon realized that the cough wasn’t related to any virus or infection. It was because the children were lacking oxygen, and their lungs were plugged with dust that possibly contained radiation particles. Many of the children waited outside for hours for the buses to arrive to bring them to the hospital. There were a lot of mistakes made [in the aftermath of the disaster], but one of the biggest was the lack of knowledge and understanding, [which resulted in] children being left outside to breathe this radioactive air. So, we started giving them oxygen. Since we didn’t have enough [individual oxygen tanks] for everyone, we made tents out of bed sheets and pumped oxygen in and had the children sit inside the tents.

The Soviet government withheld information pertaining to the explosion and its aftermath, and even spread rumors about the situation. How did this affect you?

It was very hard psychologically, especially knowing that some of the information being spread came from either government officials or through rumors. Lots of people, physicians in particular, have colleagues in different locations [that were sharing information with one another]. A close friend of mine was called into work on a Saturday, which was unusual for him. He was handed a dosimeter, the device used to measure [ionizing] radiation, and used it to measure the levels in tap water. He called me and told me not to use the tap water, not even to brush my teeth. It was nothing official, since he wasn’t allowed to tell anyone about his findings. I immediately shared this information with friends and colleagues. This is how information spreads despite all the warnings given [by the government] if you tell the truth. It was a huge risk for him to do what he did; he could’ve lost his job.

You often faced anti-Semitism as a Jewish doctor, which ultimately led to you immigrating with your family to the United States. What was that transition like coming here?

It wasn’t difficult for me, because I was by default so fond of [the United States]; I wanted to get here so badly. Plus, our family got an extremely warm welcome from the Jewish community when we arrived in Washington, D.C. We made friends in a couple of weeks, and quite a few of them are still some of our best friends. The welcoming we received took some fears off my mind, although not having a job and not having the credentials that would allow me [to practice medicine here], plus taking care of a little girl and my elderly grandmother, all contributed to my anxiety and uncertainty. Not every family had this kind of welcome. Some [refugee] families ended up in the far west where locals weren’t so familiar with immigrants and how to accept them and even if they should accept them. There was a fear that they would take their jobs. However, we were blessed, and we never wanted to leave Washington, D.C.; I considered it home from day one.

As a medical professional, how did your experience in Chernobyl prepare you for your work with the FDA developing disaster readiness protocols?

This experience taught me a lot. The main point is that people—not just physicians, but the general public—need knowledge of what’s happening. Unfortunately, in [the United States], physicians don’t have good and proper training in radiation. Without knowledge in this field, people can’t do anything, but fortunately we do have experts in the area of radiation. When I worked with the FDA, I had meetings with the Departments of Defense and Health and Human Services on how to prepare our country in case of a nuclear disaster. There are guidelines and [mock explosion] exercises that take place every other year that pretend that a nuclear explosion occurs in a major city. What I witnessed [at Chernobyl] helped me realize that strong communication between the government and the public and doctors is necessary, otherwise it can cause bad outcomes.

You compare the U.S government’s lack of preparedness during the Covid-19 pandemic to the Soviet Union’s mishandling of the Chernobyl explosion. What do think can be learned from both of these two global tragedies?

We need to analyze very critically what happened and why. Each disaster, regardless of whether it’s nuclear or a viral pandemic, has lots of things in common, and we need to be aware of this. There needs to be strong communication not only within the country, but also amongst international communities. So much depends on our preparedness, and so many deaths could’ve been avoided at Chernobyl. And the same with Covid-19. The former Soviet Union didn’t know how to prepare for such a disaster. The United States did know how to prepare, but failed to do it.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.