Around the World in Eight Plants

A new book takes readers on a journey across our planet, stopping to smell flowers and appreciate other species along the way

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/2f/3c2f74f4-b235-4716-9e37-8d8d443911b0/agave.jpg)

Jonathan Drori’s interest in plants stems back to his childhood growing up in southwest London. His family lived within walking distance of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, home to one of the most prestigious and diverse collections of botanicals in the world. His parents would take him and his brother on frequent trips to the gardens, exploring the grounds and discovering new plant species from around the world.

“My father was trained in botany but spent his career as an engineer, while my mother was interested in the aesthetics of plants,” he says. “She would carry a magnifying glass in her purse, and we’d go to Kew every week to look at the individual plants.”

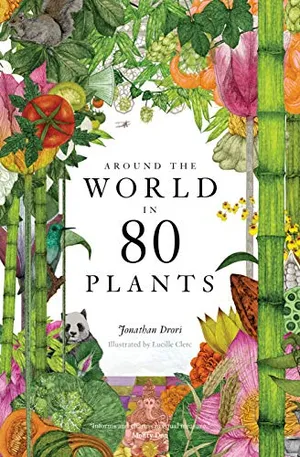

Fast forward several decades and now Drori is a botany expert in his own right, even serving as a trustee at Kew for a stint. He’s built a career as an educator, focusing on conservation, the environment and technology, and is also a prolific author. His new book, Around the World in 80 Plants, follows on the heels of his bestseller, Around the World in 80 Trees, and serves as an illustrative compendium that explains the historical and cultural significance of different plant species, from amaranth to wormwood. Using a map as his guide, he selected a range of plants from around the world, each with an interesting backstory that focuses on the cultural significance and botanical structure of each species.

Around the World in 80 Plants

Jonathan Drori takes a trip across the globe, bringing to life the science of plants by revealing how their worlds are intricately entwined with our own history, culture and folklore. From the seemingly familiar tomato and dandelion to the eerie mandrake and Spanish "moss" of Louisiana, each of these stories is full of surprises.

While Drori's new book takes a more leisurely pace, for our purposes, here is a quick spin around the globe, through eight standout plants—some of which might be growing in your own backyard.

Kelp (Scotland and the United States)

With its long tangles of sinuous leaves that bend and sway with the ocean waves, kelp (genus Laminaria) is a common sight along the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and is especially prolific in the cold waters lapping up against the Scottish and American coastlines. Kelp forests not only provide ample habitat and nutrition for invertebrates and fish, such as rockfish, crabs and jellyfish, but they also offer a number of important ingredients for us land dwellers, too. Beginning in the 18th century, kelp ash, a residue that’s the result of drying and burning kelp leaves, was used by glassmakers as soda, an ingredient that forces sand to melt at a lower temperature. “Kelp was also a prized source during World War I, and the acetone extracted from it was used to make explosives,” Drori says. Nowadays, kelp is harvested for a much sweeter reason: its alginates (part of the cell walls of brown algae) are one of the key components used to make ice cream.

Wormwood (France)

Wormwood (genus Artemisia), an aromatic herb with silvery leaves and bright yellow buds, is native to Europe and can be found growing in fields throughout the continent, but particularly in France, where it’s used as one of the main ingredients in making absinthe. Although there are different thoughts on who actually invented absinthe, according to one story it's believed that the first person to use wormwood to make absinthe was a woman in Switzerland by the name of Madame Henriod. Called the “green fairy,” absinthe is a liquor that’s been immortalized in pop culture for its supposed psychedelic properties, which have led imbibers to “go mad," Drori says. (Case in point: Artist Vincent Van Gogh lopped off his ear after allegedly partaking in a few too many rounds of the potent tipple.)

Papyrus (Egypt)

During antiquity, wild papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) grew prolifically throughout Egypt, sprouting up along the Nile River and other large bodies of water, reaching heights of 16 feet. The Egyptians were so drawn to the towering plant, with its splayed-out tufts of leaves, that they began harvesting it to eat. “Papyrus swamps were the larder of the day, they were teaming with life,” Drori says. “They didn’t have refrigeration back then, so it was a fantastic source of fresh food.” The Egyptians soon discovered that by drying the soft white pith running through the plant’s thick reeds and weaving them together, they could make paper. Word of this new commodity spread to Europe, and the rest is, well, history.

Vanilla (Madagascar)

Native to Mexico, but now grown predominately in Madagascar, vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) is one of the most expensive spices in the world, fetching $50 or more per pound. And yet there’s good reason behind the hefty markup: Vanilla is also one of the most difficult plants to cultivate. Since it doesn’t self-pollinate, vanilla’s flowering blooms must be pollinated by hand in order for them to produce pods. What’s more, the horn-shaped flowers only bloom for one day, forcing vanilla growers to search plants regularly for new flowers. Once a bloom is found, growers use a pollination technique that’s 200 years old, which involves piercing the hermaphroditic plant’s membrane separating the male and female parts of the flower and squeezing them together to transfer the pollen in what’s called “consummating the marriage.” The steep price tag for the beans has resulted in a black market. However, growers have found a way to thwart thieves. “To prevent people from stealing their beans, farmers will incise a code that identifies themselves and their farm on each pod, similar to ranchers branding their cattle,” Drori says.

Lotus (India)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2c/81/2c814ddd-b85f-4d6f-9650-45609a1789a4/gettyimages-1234989884.jpg)

Designated as the national flower of India, the lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) has been a sacred symbol of the country for thousands of years. These aquatic plants, whose magnificent blooms come in shades of pink, yellow and white, are often seen floating languidly on the surface of ponds, marshes and other slow-moving bodies of water. The lotus is a commonly depicted motif in art as well, in particular amongst Hindus who believe that Brahma, the creator of the universe, emerged from the navel of Lord Vishnu while seated on top of a lotus flower. Not only is the stunning plant cherished for its beauty, but the lotus root is recognized as an important food staple across Indian, Japanese and Chinese cuisines, calling to mind the mild vegetal flavor of artichokes, but with a much more satisfying crunch.

Chrysanthemum (Japan)

Similar in appearance to a cheerleader’s pom poms, chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemums spp.) are some of the showiest plants found in nature. The blooms come in a variety of colors and forms, with some cultivars displaying single or double layers, while others burst with spherical petals. In the United States, chrysanthemums (or simply mums) are most commonly seen during the cooler, autumn months, decorating porches alongside pumpkins and stalks of corn; however, in the Far East, where they originated, they’re a common emblem and can be seen blooming in gardens in the autumn as well as in traditional paintings. These perennials are particularly revered in Japanese culture. “The chrysanthemum is associated with perfection and nobility,” he says. “The Imperial Seal of Japan is a chrysanthemum. It’s also regarded as one of the four ‘noble species’ alongside plum, orchid and bamboo.”

Amaranth (Peru)

Amaranth falls into the category of forgotten grains, since it’s often overshadowed by more readily available whole grains like oats and rye. However, it has gained popularity in recent years thanks to being highly nutritious and a good source of amino acids. In fact, prior to the Spanish Conquest in 1519, amaranth was a staple foodstuff of the Inca and Aztec empires. The Aztecs used the seeds of the scruffy garnet plant for ceremonial purposes, mixing amaranth flour with agave syrup and molding the mixture into figures representing important deities within their culture, such as Tlaloc, the god of rain. Upon seeing this, Spanish conquistadors banned the crop, believing “the practice to be the work of the devil,” Drori says. In modern-day Peru, a popular street snack called turrones is made by popping the seeds—similar to popcorn—and mixing it with agave syrup or molasses in a nod to the Aztecs.

Blue Agave (Mexico)

Blue agave (Agave tequilana) can be found in parts of the southern United States and Central America, but it’s most frequently grown in a sunny swath of rolling hills in Jalisco, a state in the western portion of Mexico. It’s there, in a town called Tequila, where the world’s top distillers make tequila using the piñas (hearts) found at the center of the spiky blue succulents. While the leaves of the blue agave are covered in barbs and inedible, the flowers of the plant are the source of agave syrup, a clear, sticky liquid similar to honey often used to sweeten up margaritas and other drinks. Once fermented, it turns into pulque, a milky alcoholic drink similar to low-octane beer that was originally used by the Aztecs during religious ceremonies. “Drawings of the goddess of fertility, Mayahuel, can be seen in the Aztec culture depicting the deity as a being with 400 breasts dripping with pulque,” Drori says. Today pulquerias serving the drink can be found in cities across Mexico.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.