Two small, round eyes glint like shiny black sequins in the flashlight beam sweeping under the truck bed. It’s a cold, rainy September night, and the dark figure huddled in the shallow space below is barely visible—but for its striking white chest. A young girl in a bright orange jacket crouches on the wet ground nearby, trying to coax the creature out.

It’s well past the hour you’d expect kids their age to be in bed. But 9-year-old Sigrún Anna Valsdóttir, peering under the truck bed, and 12-year-old Rakel Rut Rúnarsdóttir, shining the light, don’t seem to notice the time or the cold. They’re on a mission to rescue a puffling.

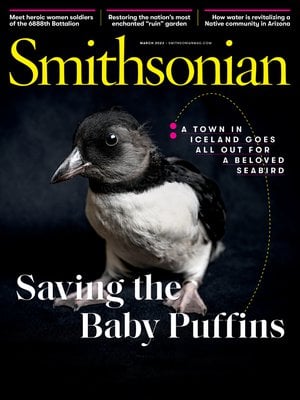

That’s the name for a baby Atlantic puffin. This one made a wrong turn and got stranded on its maiden flight. Now they need to collect it and send it safely out to sea. There’s an unwritten rule around here, I’m told. You can’t quit until the puffling is safe.

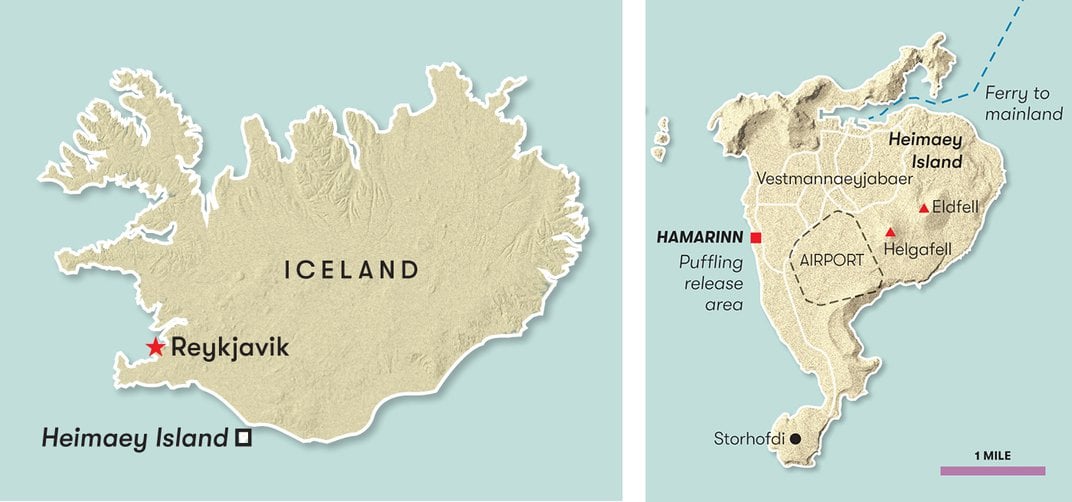

We’re in Vestmannaeyjabaer, a town of some 4,400 people perched on a roughly five-square-mile island off the southern coast of Iceland. The island, Heimaey, is the largest and the only inhabited one in the Westman archipelago—a cluster of volcanic isles, stacks and skerries that’s home to the largest colony of Atlantic puffins on earth.

These chunky black-and-white seabirds with endearing sad clown faces are known and loved worldwide. But nobody loves puffins more than the people of Heimaey. You’re never far from a puffin in this fishing hamlet surrounded by soaring cliffs. When you roll off the ferry from the mainland, one of the first things you see is a stone puffin as tall as a man. Cartoonish puffin schnozzes jut from signposts pointing you around town. You can rest on a puffin park bench or watch kids ride puffin bouncy toys on the playground. Puffin whirligigs spin in the ever-present wind.

The flesh-and-feather versions spend most of their lives far offshore in the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. But for a few months every year, they come on land to breed. As they strut around their clifftop colonies in tuxedo plumage and with upright stances, puffins look like proud little men. The species’ scientific name, Fratercula arctica, means “little brother of the North.” Puffins are lundi in Icelandic, and on Heimaey a puffin chick has a special pet name: pysja.

In March, as the days lengthen, folks here begin looking forward to the birds’ return. Over the next several weeks, well over a million puffins will arrive in the Westman Islands megacolony. Life partners, separated during their time at sea, will reunite and lay their single egg in an underground burrow dug out of the grassy cliffs. The July sea and sky will churn with birds ferrying food to their hungry chicks.

The pufflings emerge at night from their underground digs in late August and September. Most adults have already departed for winter on the open ocean, likely heading for a seabird hot spot southeast of Greenland, along with jaunts from the Arctic to the Mediterranean. Now, it’s time for the chicks to follow the moon lighting their path to the water. For the next few years, the chicks will roam the North Atlantic on their own, possibly crossing the ocean before returning to their birth colony to breed.

But on their first flight after leaving the burrow, some young birds get confused by the lights of the town and head inland instead of out to sea. Puffins are amazing swimmers, able to dive up to 200 feet deep, thanks to bones that are dense—unlike the light, airy bones of most birds. But that makes it harder for them to take flight. At sea, the water provides a runway; in the colonies, they can launch from cliffs and catch a breeze. When pufflings land on the streets, however, their new wings are too weak to get them aloft from the flat ground, leaving them vulnerable to cars, predators and starvation.

That’s where Sigrún Anna and Rakel come in. They’re part of the Puffling Patrol, a Heimaey volunteer brigade tasked with shepherding little puffins on their journey. Every year during the roughly monthlong fledging season, kids here get to stay up very late. On their own or with parents, on foot or by car, they roam the town peeking under parked vehicles, behind stacks of bins at the fish-processing plants, inside equipment jumbled at the harbor. The stranded young birds tend to take cover in tight spots. Flushing them out and catching them is the perfect job for nimble young humans. But the whole town joins in, even the police.

No one knows exactly when the tradition started. Lifelong resident Svavar Steingrímsson, 86, did it when he was young. He thinks the need arose when electric lights came to Heimaey in the early 1900s. Saving the young birds likely began as “a mix of sport and humanity,” Steingrímsson tells me in Icelandic translated by his grandson, Sindri Ólafsson. Also, he says, people probably wanted to sustain the population of what was then an important food source. (Puffin hunting remains a cherished cultural tradition here, but today the season length is largely restricted.)

As the town and its lights grew over the years, so did the number of wrong-way pufflings, says Steingrímsson, who once jumped into a freezing cold well to rescue one. These days, however, there are far fewer pufflings to rescue. Major puffin colonies from the British Isles to Norway have been struggling to produce young for years. In the Westman colony— birthplace of nearly one in four puffins in the North Atlantic today—the population has plunged by half since 2003. These heralds of the northern spring are now listed as endangered in Europe by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

A quarter century ago, when Sigrún Anna’s father, Valur Már Valmundsson, was a boy, he rescued as many as 100 pufflings in a night. His daughter and the other kids out tonight won’t see that many in an entire season. That’s one reason they’re so intent on rescuing this one under the truck bed. The girls stand guard as Valmundsson, a burly chef on a commercial fishing boat, rakes a long metal pole toward the little bird. Inch by inch, the puffling backs away.

Finally, after half an hour, the chick darts out the other side. It moves fast on its two webbed feet, but the girls are faster. Sigrún Anna wraps the bird in her mittened hands and shows it to me with a shy smile. Its sequin eyes sparkle in its gray face as it regards me calmly. Puffins’ kabuki faces, flashy bills and orange feet are attire for breeding, which this chick won’t begin doing until it’s 4 or 5 years old. Tonight, it will sleep on a bed of grass in a cardboard box. Tomorrow, the girl in the bright orange jacket will stand on a cliff on the west side of the island. She’ll toss the puffling into the air and watch it sail off to sea.

Driving through the wee hours of a cold Nordic night searching for pufflings is a surprisingly warm experience. As they roll up and down the quiet streets, shining flashlights out the car windows, Sandra Síf Sigvardsdóttir and her sister Berglind Sigvardsdóttir talk about everything under the sun.

“It’s like going to a shrink in a car,” says Sandra Síf, a vivacious mother of three young girls who works as an aide for people with disabilities. She and Berglind, an EMT and mother of four, have been rescuing baby puffins since they were practically babies themselves, and they began teaching their own children before they were old enough to walk. Their children’s schoolmates call the sisters the Puffling Queens.

Around 1:30 a.m., on one of several nights I spend patrolling with them, two of Sandra Síf’s daughters—Íris Dröfn Guðmundsdóttir, 8, and Eva Berglind Guðmundsdóttir, 5—drowse in the back rows of her minivan. Berglind is out in another car with her 14-year-old son, Arnar Gauti Eiríksson. The sisters chat on the phone and make plans to meet up later, after the children have been put to bed.

We slowly cruise past closed shops and dark restaurants. A man on a street corner waves us over. “Are you searching for pufflings?” he asks. He hands Sandra Síf a chick he just found as he walked home from a wedding. We head toward the harbor, passing kids on scooters. Two teenage boys tote a cardboard box. A car creeps along the waterfront with a small child’s face looking out the back.

Earlier that night, Sandra Síf’s daughters gave me a lesson in how to rescue pufflings. “Bring a flashlight. And gloves. And a box. Look for a beak,” the girls instructed in Icelandic, translated by their mother. “We make a noise with our feet, and then listen.” Why do you do it? I asked them. Why give up sleep for days to prowl around in the dark looking for lost birds? “Because it’s fun,” said Íris Dröfn. “Because they’re so cute,” Eva Berglind chimed in.

“If somebody says, ‘Tell us one thing that’s on your island,’ probably 99.9 percent will say, ‘puffins,’” their mother replies when I ask her later. “Everything here revolves around puffins.”

Now it’s 2 a.m., and we’re still empty-handed. “When I was a kid, they were just pouring down,” Sandra Síf recollects wistfully. Finally, at nearly 2:30 a.m., we spot a puffling amid piles of fishing nets and ropes twisting like snakes. Sandra Síf wakes up Eva Berglind, who climbs out of her car seat and snatches the little bird. She’s just gotten back into her seat when we see another one. She clambers out again.

When the birds are secure in their cartons, I ask Eva Berglind how she feels. “Freezing,” she says, rubbing her hands. “And tired.” The little girl yawns and closes her eyes, a whisper of a smile on her sleepy face.

A puffling dangles in a duct-tape-wrapped cylinder. It’s part of a weighing contraption in the Puffling Patrol headquarters, where rescuers can bring chicks to be checked out and registered before release. Rodrigo Martínez Catalán, a research assistant with the South Iceland Nature Research Center, frowns as he records the bird’s weight and wing length. Another small one. It will need to stay and be fed until it grows large enough to let go.

Catalán started the 2022 season with high hopes. The breeding catastrophes that had plagued the colony since 2003 had recently started to improve. For the previous few years, most of the Westman Islands megacolony’s 1.1 million burrows had produced big, healthy chicks. The 2021 crop had numbered roughly 700,000, and most were expected to survive.

“The parameters were all giving the green light,” said Catalán, a wildlife biologist who moved here from his native Spain. He and colleagues were hopeful that a turnaround was underway. But halfway through the summer of 2022, nearly half the chicks had died—apparently from starvation, Catalán’s boss, biologist Erpur Snær Hansen, tells me. The pufflings Catalán was seeing at the center were lighter than average, with lower odds of surviving their first winter. And the number of rescues was down. The season was beginning to look more like a relapse than a rebound.

Iceland’s puffin population has long waxed and waned, following natural ocean temperature cycles, says Hansen, the nature research center’s director. As Iceland’s chief puffin scientist, Hansen makes a twice-yearly circuit of the nation’s colonies to report on the season’s breeding success. He has compiled more than a century of Westman Islands sea surface temperature and hunting records to create the world’s longest puffin population data set. Historically, reproduction slumped when a warm phase tanked the supply of sandeel—a nutritious, pencil-shaped fish that the Westman Islands megacolony relies on to feed its chicks. Sustained higher temperatures perturb sandeel metabolism and reproduction, causing a scarcity of prey close enough to the colony for parents to reach while tending young. Some years, most chicks have starved. Other years, most of the colony has skipped breeding altogether. Then, when sea surface temperatures moderated, puffling numbers ramped up again.

Puffins are a long-lived species—topping 25 years on average and up to a venerable 36—so colonies can withstand some years of breeding failure and still have adults around to try again. But nothing in the records stretching back to 1880 comes close to the cataclysmic population crash this century, Hansen says. For a decade and a half starting in 2003, chick production was below sustainable population levels. Scientists are investigating the reasons, but it looks like normal fluctuations are being amplified and disrupted by climate change. “We are seeing something extraordinary,” Hansen tells me. “Changes that just slap you in the face, they’re so big.”

Seabird babies face a tight schedule in the short northern summers. After around six weeks in the egg, pufflings have roughly six weeks to grow and fledge before winter returns. Yet in recent years, puffin breeding in the Westman Islands has sometimes been more than two weeks delayed. Hansen thinks the delays are linked to late starts for the spring ocean productivity cycle. If the puffins began breeding at their usual time while food sources lagged behind, their chicks would arrive without enough to eat. When breeding is postponed, however, chicks are robbed of precious growing time.

Breeding disruptions are also underway in Norway, says Tone Reiertsen, a seabird biologist with the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. In the Barents Sea colony she monitors, the puffins have been prolonging their pre-breeding period, taking more time to fatten up in preparation for the rigors of producing eggs and rearing chicks. But this does not seem to increase the colony’s breeding success, she says. Reiertsen is investigating the grim possibility that the changing environment may exceed breeding puffins’ ability to adapt. “They still try to breed, and the chicks are dying.”

Shifting ocean circulation is at least partly to blame for the puffins’ plight, Hansen and other scientists believe. In the subpolar gyre south of Greenland, cold, nutrient-rich Arctic water mixes with warmer, nutrient-poor water from the south. By controlling the mixture, the gyre governs the annual spring bloom of phytoplankton, the base of the ocean food web. For most of this century, the gyre has been weak, Hansen says—allowing more southern water into the system, which dials back the supply of silicate, a mineral essential for the tiny organisms’ growth. The Westman colony’s breeding disasters correspond to low-silicate years, Hansen’s observations find.

At sea, climate change is increasingly fueling extreme storms that prevent birds from feeding, which causes mass die-offs. Puffins and other seabirds also face threats from overfishing, marine pollution, invasive species and more. Rising numbers of voracious mackerel in Icelandic waters, for instance, may outcompete the puffins’ prey. And some puffins may be exceptionally vulnerable to the changing environment, due to their unusual habit of molting twice—leaving them flightless for more than two months—during their time at sea.

Nonetheless, Hansen says he’s hopeful for Westman Islands puffins’ future, at least in the short term. Both silicate levels and chick production have been ticking up in the past few years. And despite the dramatic drop in 2022, when the total number of pufflings rescued ended up less than half that of the year before, Hansen says it still surpassed the “abysmal horror” years when almost no chicks survived. “There is a real increase,” Hansen says. “It’s really good compared to zero.”

At a sea cliff called Hamarinn, a parade of families arrives with boxes. Crowds watch as children stand on a low stone wall, flinging chicks skyward to spread their wings and glide down to the water below.

It seems as if all of Heimaey—and then some—is at Hamarinn at some point during my visit. A group of international students from Estonia liberates a puffling found on an island tour. A tourist from Wisconsin snaps photos. Families with members too young or too old for the Puffling Patrol come to watch.

Ágústa Ósk Georgsdóttir and Sunna Tórshamar Georgsdóttir, two sisters in their 20s, are here many days with a trunkload of rescued birds. “I feel proud that I helped it get to the ocean,” Ágústa says as she watches one fly off. “And maybe someday I’ll rescue its pufflings,” Sunna adds. Together, the sisters, who work as caregivers at a nursing home, will rescue 125 pufflings this season.

Hope is the thing that drives the people of Heimaey to care for pufflings. I see it in Berglind, who’s taken one of the scrawny ones home to fatten it up. Six times a day, she cuts capelin fish into baby-bird-sized slices and feeds it to the chick. “The pufflings need us to help them,” she says, smiling as we watch the little bird swallow a slice whole and wriggle to work it down. “It’s kind of a mothering instinct thing.”

I see that feeling in the tattooed hipster who hops out of his car in the middle of the night to pick up a puffling that has just fallen from the sky. It’s there in the high school girls driving around with a puffling in the back seat—and the schoolgirl bicycling to Hamarinn with a puffling in one hand. It’s shared by the teachers, who put up with sleepy students because they were out late on Puffling Patrol themselves.

The reward is setting a bird free. Íris Dröfn strides with solemn purpose atop the rock wall with a puffin cap on her head and a puffling in her hands. Her youngest sister, 10-month-old Sara Björk, watches wide-eyed, looking eager to get in the game just as soon as she can.

“She’s got no choice,” Sandra Síf says. “If she’s going to be my baby, she’s got to love pufflings.”

It’s a passion Sandra Síf loves to share. Before photographer Chris Linder and I leave the island, she meets us at the ferry with a cardboard box. Inside is a puffling for us to release during our ride.

Now, as the promise of spring stirs puffins’ yearning for land, the folks of Heimaey are eager for their return. “It is a big part of the whole summer,” says Jóhann Freyr Ragnarsson, a retired mariner who grew up rescuing pufflings. “It is news in the local newspaper when the first puffins come to the cliffs.”

Perhaps a few years from now, one of these returning birds will be the puffling I saw last fall, tossed into the air by a young girl in a bright orange jacket, her arms held aloft as she watched it fly off over the ocean, full of wonder and hope as she saved one small part of the world.