Graffiti Left by Soldiers Repairing Hadrian’s Wall Will Be Immortalized in 3-D

Historic London calls the etchings “some of the most important” along the empire’s sprawling 73-mile northern border

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/08/64080bfd-484c-450a-8e9b-3c072524a13a/historic_england.jpg)

In 207 A.D., a group of Roman soldiers tasked with repairing portions of Hadrian’s Wall chiseled a lively array of drawings and inscriptions into a nearby Cumbrian quarry. The site, rediscovered during a routine 18th-century inspection, remained accessible to the curious eyes of the modern public until the 1980s, when the path leading to it collapsed.

While continued erosion has made it so you still can’t visit the area in person, a joint campaign between Historic England and Newcastle University is opening up a new way for ancient graffiti fans to take in the heritage landmark, dubbed the Written Rock of Gelt. As Mark Brown reports for the Guardian, archaeologists are in the process of rendering an ambitious 3-D record of the rare marks that will preserve the site like never before.

After carefully scaling the quarry walls with the help of ropes and pulleys, the plan is to give the surface of the quarry a cleaning, and then use structure-from-motion photogrammetry to record the etchings, which will be made publicly available via the 3-D modeling platform Sketchfab.

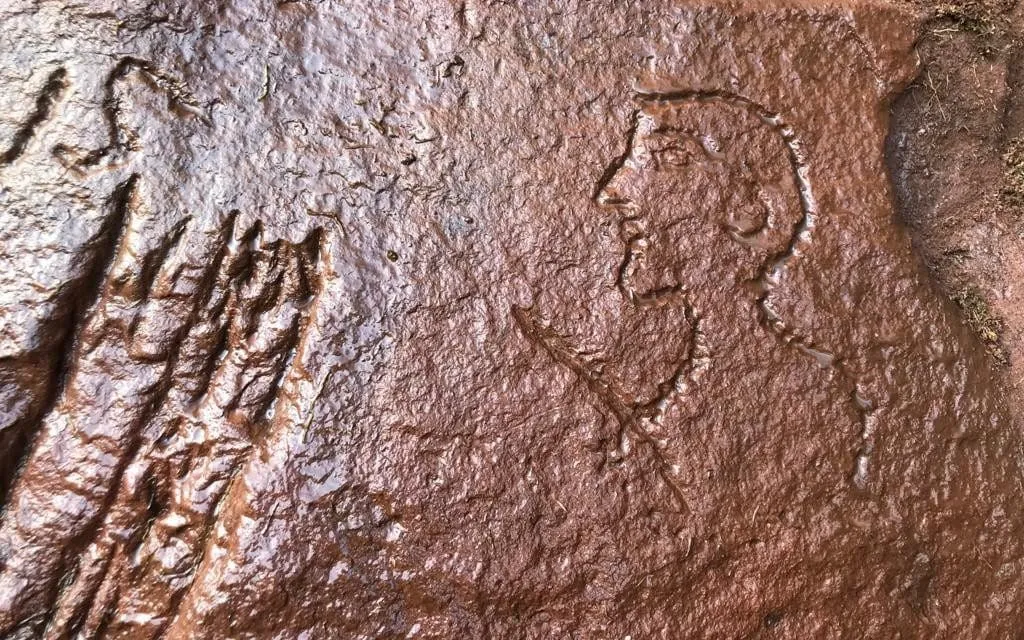

Already, according to the Telegraph’s Patrick Sawer, the team’s preliminary work has revealed several previously unnoticed inscriptions. Two shallow relief busts spotted on the rock ledge could represent self-portraits left by the soldiers, or perhaps a mocking caricature of the men’s commanding officer.

A third marking is less open to interpretation. But the unabashedly phallic symbol isn’t simply a reminder of mankind’s enduring juvenile tendencies: Michael Collins, Historic England’s inspector of ancient monuments for Hadrian’s Wall, tells Cahal Milmo of I News that the Romans generally viewed the phallus as a good luck charm.

Indeed, the Rock of Gelt phallus is just one of many associated with the Roman Empire’s sprawling 73-mile northern border. In an interview with CNN’s Emily Dixon, Newcastle archaeologist Rob Collins says he has identified 57 other etchings of male genitalia scattered across the length of Hadrian’s Wall. Expanding on what Mike Collins of Historic London said, he explains that the symbol was “used to ward off misfortune and bad things in general."

Just as crude renderings of phallic symbols found in bathroom stalls and school notebooks tell us something about how we understand the meaning of the image today, context in ancient times also informed the way it was viewed back then. "We know [its meaning] both from the way in which Romans have written about the phallus relative to ritual and religion, as well as how these symbols are encountered by archaeologists," the Newscastle team member tells CNN.

Text scrawled alongside the graffiti also offer further insights into the soldiers’ lives. One line stating “in the consulship of Aper and Maximus,” for example, enabled historians to date the graffiti to its exact year—the only time that both men served as Rome’s consuls. Placing the repairs in this historical context, the Guardian's Brown notes that during 207 A.D., Emperor Septimius Severus was in Britain leading Roman soldiers against rebelling tribes. During his reign, Severus commissioned extensive improvements to the wall that left later historians uncertain whether he or Hadrian had originally built it.

A second inscription indicates the soldiers’ role in Severus’ vast army, yielding a rough translation of “detachment of the Second Legion Augusta, the working face of Apr … under Agricola.” A third marking spells out “EPPIVSM,” according to the Telegraph, and is believed to represent the name of a specific worker, one Eppius M.

“These inscriptions ... are probably the most important on the Hadrian’s Wall frontier,” Collins says in a Historic England statement. “They provide insight into the organisation of the vast construction project that Hadrian’s Wall was, as well as some very human and personal touches.”

While digitization efforts are just ramping up, eventually, the team hopes to produce a 3-D model that simulates light being shone at various angles, affording viewers an even more detailed 360-degree portal into the past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)